Two years have passed since Congress approved nearly $190 billion to help the nation’s schools respond to the pandemic. Rather than prescribe uses as Washington did with the Race to the Top program and other education recovery funds a decade earlier, Congress laid out a broad set of allowable uses and left spending decisions largely to state and local education agencies. Where is the money going?

To answer that question and to explore why visibility into local pandemic-recovery spending has been lacking, FutureEd examined in depth local outlays in California, home to 12 percent of the nation’s public school population and recipient of more federal recovery funding than any other state—$23.4 billion in three installments of federal Elementary and Secondary Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds.

The state has spent nearly three-fifths of that money and has among the most demanding state ESSER reporting requirements, expecting local education agencies to provide quarterly breakdowns of expenditures under the third and largest tranche of ESSER spending in 29 categories.

FutureEd studied local expenditures posted in California’s ESSER III spending portal, interviewed state and local authorities and, where possible, compared local education agencies’ spending trends to the information in spending plans that local education agencies were required by Congress to submit nearly two years ago and that FutureEd analyzed in a series of 2022 reports.

We found both encouraging trends and cause for concern.

Congress approved ESSER III funding in March 2021 through the American Rescue Plan. While schools used much of their ESSER I and ESSER II monies approved in 2020 on health and safety and distance learning, the hope has been that ESSER III would aid academic recovery. California received $15 billion in ESSER III funding, $13.5 billion for local education agencies and $1.5 billion for the state.

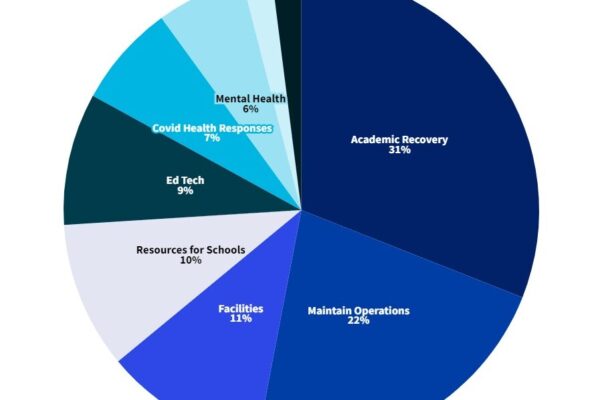

We found that the largest share of the local ESSER III spending reported through March 2023, the end of California’s most recent reporting period, has supported efforts to help students rebound from the pandemic academically, in line with federal aspirations for the funding. School districts and charter schools have also spent extensively on mental health support, a key post-pandemic need, and school facilities and educational technology—trends we found in our earlier analyses of expenditure plans.

Some local education agencies, though, have struggled to use their federal assistance. And much of what has been spent remains shrouded in broad categories that provide little transparency into what local educators are doing with the federal funding, much less the extent to which the money is helping students.

Following are details on the pace of ESSER III spending in California, how school districts are investing the federal aid, and the troubling lack of transparency in a great deal of the state’s local ESSER spending.

Pace of Spending

The latest data from the U.S. Department of Education’s spending portal shows that California’s education agencies—on the state and local levels—have drawn down $6.3 billion or 42 percent of their $15 billion in ESSER III funds as of the end of April, on top of 87 percent of their earlier rounds of federal money.

The federal portal does not provide a breakdown of how the money has been used. But California requires its more than 1,700 local education agencies (including school districts, charter school organizations, and county offices of education) to submit more detailed quarterly reports on their ESSER spending to the state’s Department of Education, and the agency’s ESSER III portal shows $5 billion in local expenditures from the final round of funding through March 2023.

That means California’s local agencies would have to spend or obligate as least $1 billion a quarter to meet the federal government’s September 2024 deadline for committing the ESSER III aid—a pace they have met for three of the past four quarters.

Beyond the statewide trends, FutureEd found that the pace of local ESSER III spending varies widely across school districts.

At least 131 of the state’s local education agencies have reported spending all their ESSER III funds and another 235 have reported spending at least 80 percent of their funding. Many of these fast-spenders received modest sums because they have small student populations or few students living in poverty. (The ESSER money is distributed using the federal Title I formula, which provides more support for schools with high concentrations of poverty.) The average allocation for those spending their funding completely is $663,000, compared to the statewide average of nearly $8 million.

At the other end of the spectrum, some 60 local education agencies hadn’t spent any of their funds through March, and another 108 had spent less than 10 cents of every ESSER III dollar they received. The districts that have spent nothing have on average $1.2 million to spend, while those under the 10 percent mark average about $8.1 million.

The low-spending category includes several large districts, though there remains considerable variation among California’s major school systems. San Francisco Unified, one of the state’s largest local education agencies, had used nearly 80 percent of its $94 million in ESSER funds. Los Angeles Unified had spent about 37 percent, and Long Beach Unified School District spent just 5 percent of its ESSER funding through March.

The lagging spending rates don’t necessarily mean local education agencies won’t use their ESSER monies on schedule. Renee Arkus, Long Beach Unified’s executive director of fiscal services, told us that while the California ESSER portal reflects only $11 million in spending from the district’s $212 million ESSER III allotment, the district plans to spend the money over the next year and a half as a part of a six-year, $500 million improvement blueprint that draws on money from a range of sources. Arkus says Long Beach is using up the first two rounds of ESSER money, along with millions in state aid, before tapping ESSER III funding. “I put them in order, first in, first out, by expiration,” she says.

Spending Priorities

We examined spending trends in five areas: academic recovery, mental health, technology, facilities, and staffing.

Academic Recovery

California’s local education agencies spent nearly a third of their ESSER III funding through March on helping students rebound academically from the pandemic—their single largest investment and 50 percent more than they are required by federal law to spend in that area.

That includes at least $303 million on summer learning, afterschool and extended time programs and $74 million for tutoring. Other academic recovery expenditures appear in generic categories, such as “addressing learning loss” and “other learning loss interventions,” making it difficult to know precisely how school districts, charter school organizations, and county offices of education are investing their academic recovery monies.*

Nineteen percent of California localities invested ESSER III funding in tutoring through March, compared to the 23 percent that earmarked money for tutoring in their plans. The lower-than-expected ESSER III investments in tutoring could also mean that some local agencies are funding these programs with new state aid.

On top of the federal money, the California legislature has allocated $4 billion in grants for districts and charters through the state’s Expanded Learning Opportunities Program, much of which is going for afterschool and summer efforts and tutoring. That includes much of the state’s share of ESSER aid (90 percent of ESSER monies go to local education agencies; 10 percent goes to state departments of education) as well as other state dollars.

There is no tracking system for how the state expanded learning aid is being used, but some districts are funding their programs with state money and using the more flexible federal dollars for other priorities, says Mary Briggs, the California School Board Association’s senior director of research and education policy development. “It’s not that they’re not doing those programs; they just are funding them with the more restrictive state funds,” she says.

Mental Health

California school districts and charters spent nearly $314 million—about 6 percent of their total ESSER III spending so far—on student and staff mental health services through March, with about 46 percent of districts spending on this priority.

Some have made very large investments in the area. The Lancaster Elementary School District north of Los Angeles spent more than $12 million, about half of all its expenditures and a quarter of its overall allotment, on mental health services. Los Banos Unified near Monterey spent $8.9 million, nearly three quarters of its expenditures. About 216 districts and charters used $27 million for social-emotional learning curricula through March, counted in the California portal and our analysis as learning loss expenditures.

The portal doesn’t break down what sort of services are being deployed, but 44 percent of California districts and charters noted in their 2021 spending plans that they were going to bring in psychologists and mental health professionals, either on contract or as staff. “I think for a lot of districts, they have relied on contract workers or telehealth programs, in part because they don’t have the labor pool locally that can meet their needs, they can’t provide commensurate compensation or because these are one-time funds,” Briggs from CSBA says.

ESSER III spending on student mental health has accelerated faster than other priorities in recent months, increasing from $24 million in the final quarter of 2021 to $66 million in the final quarter of 2022 to $105 million in the first quarter of 2023. This comes amid nationwide reports of increases in behavioral issues in schools and mounting depression and anxiety among students, especially young women.

In California, ESSER monies for student mental health support are being augmented by state revenue and mandated insurance plan spending. The Los Angeles County Office of Education, for instance, is offering virtual mental health counseling to all interested students, a telehealth option paid for by a partnership with a public agency, L.A. Care Health Plan, and health insurance provider Health Net. In addition, California is investing in a pipeline to develop more school counselors and social workers, since staffing shortages have limited the ability of districts to bring in mental health professionals.

Technology

Educational technology accounted for more than $430 million in ESSER III spending in California through March, even though many districts spent their earlier rounds of federal funding equipping schools and students with devices and wifi to support distance learning.

More than half of districts and charters reported spending in this category by the end of March, including Redondo Beach Unified, which has used $1.1 million of the $1.2 million it has expended on technology. West Contra Costa Unified has used $9.5 million or nearly half of its total expenditures on technology.

The California ESSER portal doesn’t provide detail on types of technology spending, but local education agencies’ 2021 ESSER plans prioritized computers and mobile devices, instructional software, and technology to support distance learning. The ESSER III spending may reflect these priorities as well as hardware replacements, software updates, and contract extensions with technology providers.

Facilities and HVAC

The California portal includes more than $540 million in ESSER III spending on facilities and repairs, categories that include ventilation and air quality projects, as well building improvements to reduce risk of virus transmission.

Heating, ventilation and air conditioning projects (HVAC) comprise slightly more than half of that total. The Oxnard Union High School District along the coast north of Los Angeles spent $19.3 of its $24.5 million, almost all of that on HVAC projects. Overall, 25 percent of California’s local education agencies made HVAC investments through March, compared to 50 percent that included the category in the California plans we reviewed.

The disparity may reflect shifting priorities or simply the time it takes to get some complex facilities projects off the ground. Some districts report challenges using federal money for the projects, given federal rules on safety standards and prevailing wages. Rising costs and supply chain issues are also slowing down facilities projects, says Arkus, the Long Beach fiscal services director. The district has pushed some projects later into 2024 but still expects to commit funding by the September ESSER III deadline, she said.

About 34 percent of California local education agencies have spent on other facilities repairs, about the same as the 35 percent in the plans. These include Alvord Unified in Riverside County, which has put $25 million of its $41 million ESSER allotment toward school building repairs.

Staffing

Staffing represented local agencies’ highest priority in their 2021 ESSER spending plans, appearing in 328 of the 625 California district and charter plans we reviewed. But it is difficult to get a clear sense of actual local spending on staffing from the California ESSER portal.

While some staffing costs are reflected in expenditures by function—such as tutoring, mental health and extended-time programs—there are no specific categories that capture bonuses, academic coaches or professional development for teachers and support personnel, staffing priorities included in many California spending plans.

For instance, the Enterprise Elementary School District in Redding has spent almost all of its ESSER III dollars on hiring additional classroom teachers to reduce class sizes, bringing counselors to every elementary school, and hiring temporary distance-learning teachers. The district also provided two years worth of retention bonuses earlier in the pandemic. “The majority of our funds went toward staffing because really, it’s the people that make the difference with our students and student achievement,” TJ Hurley, assistant superintendent of business services, told us.

Many local education agencies, though, have struggled to find the staff they want. A 2022 CSBA survey found that 91 percent of the state’s school districts reported challenges in filling vacant or new positions.

Lack of Transparency

Beyond these specific priorities, the California portal includes a general category called “Other activities necessary to maintain operations,” into which 1,130 districts and charters have reported $1.1 billion in spending—or about one fifth of the local education agencies’ ESSER III expenditures so far. The fiscally challenged Oakland Unified School District has put $30 million of the $52 million it has spent so far into this category, and press reports indicate the district is using the money to balance its budget and pay utilities.

Another general category, “Resources for individual schools,” contains $516 million in spending from 912 districts. That includes $207 million of Los Angeles Unified’s $960 million in ESSER III expenditures.

These and other vague classifications have prompted criticisms of why California isn’t collecting more detailed information to monitor how districts and charters are spending their federal aid—and why the federal government isn’t providing data in a more timely fashion.

The U.S. Education Department required every local education agency to submit detailed ESSER III spending plans to their state department of education in 2021 and then tasked states with tracking local spending on uses allowed under federal law.

Under the system, states submit to federal officials every month total ESSER money reimbursed to localities and the state. At the end of each school year, they include ESSER spending in a report, which includes more-detailed descriptions in such categories as learning loss, physical health and safety, mental health support, and “operational continuity.” The information is broken down further within those areas by expenses for personnel, supplies, debt services and other categories. The annual reports also indicate whether local agencies are pursuing various learning-loss priorities, such as summer schooling or tutoring.

The monthly data on each state’s aggregate local reimbursements is updated regularly in the U.S. Department of Education’s portal. But release of the more detailed annual analyses lag far behind expenditures: States need time to complete their accounting, and the federal department cleans and compiles the data. As a result, district-by-district spending for fiscal year 2021, essentially the 2020-21 school year, wasn’t released until February 2023.

The department’s Institute of Educational Services has been releasing School Pulse Panel polls that share data on how many districts are pursuing such options as tutoring, afterschool programs and mental health support. And last fall, federal education officials expanded their efforts to gather information on local ESSER spending through the voluntary annual financial surveys that state and local education agencies receiving federal funding submit to the U.S. Census Bureau. But the release of that data also lags spending by at least a year.

California is among 31 states that have created their own ESSER III portals to supplement the federal government’s reporting. But the states vary widely in the level of spending detail they provide. And 19 states report no details publicly on how ESSER money is spent.

California’s 29 spending categories provide greater detail than is available in most other states’ portals, especially on efforts to address learning loss. But many of the portal’s categories are so general as to be largely unhelpful. Together, they largely fail to provide the transparency parents, policymakers and taxpayers would need to fully evaluate how and how well local education agencies are spending the vast sums of federal pandemic-recovery funding they’re receiving.

Consider San Francisco Unified. It had spent $74 million of its $94 million ESSER III allotment by the end of March. But nearly all of that is in a broad category called “other activities that are necessary to maintain the operation and continuity of services in LEAs and to continue the employment of their existing staff.” That language is taken directly from the allowable uses provided in the federal law but offers little clarity about where the money is going.

In its spending plan, the district said it would use $15 million for summer learning programs and literacy support to address learning loss. Beyond academic recovery, the district earmarked about $16 million for special education support, $10 million for family engagement, and $2.3 million for student transportation. Most of the remainder—$39 million—was set aside to “support core operations,” an allowable if vague category. The district narrowly avoided a state takeover in late 2021, and state officials say they remain concerned about its deficit spending.

In some places, spending in that broad category reflects significant projects made possible by the federal aid. Kepler Neighborhood School, a charter school in Fresno, has spent 70 percent of its $875,000 allotment—more than half of that in the broad “other activities” category. Much of that money has gone to replacing an out-of-date internet system within the school, an expense the 400-student charter couldn’t afford before receiving the federal money, says Rickie Dhillon, the school’s superintendent. “For small school districts like us, the ESSER funding really opened doors for us to do things we couldn’t do,” she says.

Jeremy Anderson, a CSBA policy analyst, says that the lack of clarity in local education agency reporting may stem in part from the challenges in classifying spending. “If I’m a school that has an online afterschool tutoring program, and part of that is giving the students laptops and Wi-Fi, where as a district am I going to categorize that spending? Am I going to do it in ed tech, in learning loss, in tutoring?”

The reporting burden ESSER places on already overwhelmed local school officials may be another factor. “With California’s small districts, one of the things that comes through loud and clear in our survey data is people have reported feeling so overwhelmed by the impact of multiple quarterly reporting requirements,” CSBA’s Briggs says. “Many have noted that due to the size of their administrative staff, the demands strained their resources at a time when they were contending with overwhelming challenges.”

Beyond setting reporting requirements, federal authorities require states to audit a sample of local education agencies annually to ensure they are spending ESSER and other federal aid in compliance with the law. The California Department of Education divides its local agencies into four cohorts and conducts audits of selected school districts in two of those cohorts each year. Officials did not say how many districts they expect to audit each year.

In the Stockton Unified School District, an employee’s complaint about handling of ESSER money led to a state audit and allegations of criminal misconduct. In late April 2023, state and federal officials announced they would launch a criminal investigation.

California Department of Education officials have conducted additional oversight of local Covid-relief spending, including investigating any education agency after “media reports that would lead CDE to have cause for concern,” Natasha Middleton, the department’s federal policy liaison told us.

Local education agencies face the challenge of spending their ESSER aid before the late 2024 federal deadline without making financial obligations that hamstring them once the federal money is spent. “Most of our districts are projecting declining enrollments,” says Anderson of CSBA. “And because of that, you might start seeing a reticence to put a lot of money in long-term programs, because they’re going to hit a cliff potentially in that funding.” High chronic absenteeism rates also impact funding, since the state’s funding formula is based on daily attendance averages.

In such an environment, it’s tempting for school districts and charters to use federal ESSER aid to prop up their budgets rather than add new initiatives, something they’re allowed to do under ESSER legislation as long as they meet the Congressional mandate to spend 20 percent of their ESSER III funds on academic recovery. Reporting through March suggests that California’s local education agencies as a whole have met that threshold. But many individual localities have not. And the opacity of the state’s ESSER reporting system makes the extent of local agencies’ use of ESSER monies to buttress their operating budgets rather than support students’ pandemic recovery nearly impossible to know.

The limited transparency in ESSER spending in California—a state with reporting requirements that are among the strongest in the nation—is striking, given the vast sums of public funding involved and the extent of students’ needs in the wake of the pandemic. And it suggests that California and other states should do more to protect students and taxpayers through more extensive reporting and increased auditing of local ESSER spending.

Congressional leaders’ inclination to push aid to states and localities quickly and let them establish their own spending priorities in response to local needs may have made sense in the moment. But that emphasis on local prerogative has left the nation without a clear sense of whether the vast ESSER resources are fully focused on helping students.

*California asks local education agencies to report monies spent to meet the federal requirement for using 20 percent of their ESSER III aid to address learning loss and any additional spending on learning loss with the remaining 80 percent of funds. When localities report spending on learning loss in both categories, we have combined the figures for our analysis. Click here to learn more about the spending categories.