As the deadline nears for allocating the third and final round of federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds, concerns are mounting about what the financial future holds for school districts nationwide. Amidst this uncertainty, some districts have focused their efforts over the past three years on investing in an area important to student success, but one that won’t require major budget cuts when pandemic recovery funding ends: school facilities. In Mississippi, school districts are using the largest share of their $1.5 billion ESSER III allotment to improve the long-neglected spaces where students learn.

While some may associate spending on school facilities with flashy sports complexes and state-of-the-art buildings, the reality is that schools nationwide have long grappled with aging infrastructure and outdated facilities in need of comprehensive renovations. For states like Mississippi with historically low educational spending, the one-time infusion of federal funds presented a unique opportunity for districts to not only address immediate Covid-19 concerns but also tackle long-standing renovation needs that predated the pandemic. This analysis, the latest in a series of FutureEd reports on state and local pandemic-response spending, draws on Mississippi Department of Education data to explore how school districts in one of the nation’s poorest states have used federal ESSER III funds to address long-standing inequities in school facilities, a significant barrier to student success.

The Need for Improved School Facilities

Children spend a significant portion of their time—on average, seven hours a day, five days a week, and 36 weeks a year—in school. The quality of their physical environment impacts their ability to learn and thrive, yet many school buildings, especially in underserved communities, fail to provide healthy and productive spaces for students.

A 2020 Government Accountability Office report revealed that about 54 percent of public-school districts need to update or replace multiple building systems or features in their schools. Specifically, an estimated 41 percent of school districts must address issues with heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems in at least half of their schools, impacting roughly 36,000 schools nationwide. A quarter of districts require updates or replacements for other critical building systems, including interior lighting, roofing, safety and security systems, and plumbing in at least half of their schools.

Despite these pressing needs, districts consistently underinvest in the maintenance and improvement of school buildings. The 2021 State of our Schools report, a joint publication of the 21st Century School Fund, the International WELL Building Institute, and the National Council on School Facilities, highlights a significant and growing gap between current expenditures on school infrastructure and actual need, estimating an annual underinvestment of $85 billion—a number that has grown by $25 billion since 2016, adjusted for inflation.

Poor school facilities are not evenly distributed, with low-income, Black and Brown, and rural students disproportionately attending schools with substandard conditions and outdated resources, creating and perpetuating inequitable learning environments. This inequity is structured into the way we fund our schools, notes Mary Filardo, executive director of the 21st Century School Fund, a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving public school facilities. “[The funding] is very local, which means it’s the most inequitable,” Filardo says. “The most regressive sort of funding for education in K-12 is the capital.”

High-poverty districts, on average, invest 37 percent less per school in facilities improvements than their low-poverty counterparts, disproportionately affecting Black, Hispanic, and Native American students who are more likely to attend high-poverty districts. High-poverty districts in rural areas invest even less on average than those in urban areas.

The Mississippi Model

Mississippi’s education infrastructure needs reflect the national trend. Facing an annual shortfall of $619 million in school facility investments, many of the state’s school districts, especially those in high-poverty areas, are using their portion of Mississippi’s one-time, $1.5 billion ESSER III allocation to address longstanding facilities underfunding.

As of March 2024, Mississippi districts have spent nearly 60 percent of their total ESSER III funds, with a substantial portion—$362.6 million, or 42 percent—dedicated to facility-related priorities, far exceeding the National Council on School Facilities’ recommended 15 percent threshold. Some districts (20 out of 146) have spent over 70 percent of their funds so far on facilities and maintenance.

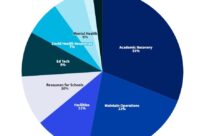

The majority of this spending, amounting to $296.8 million, is dedicated to building reconstruction and remodeling projects such as HVAC upgrades and replacements, bathroom renovations, and roof repairs. Spending on maintenance and upkeep follows at $27.6 million, with new building purchases and construction at $20.5 million and architecture and engineering fees at $14.8 million. By comparison, districts spent less than $1.3 million on non-structural elements such as lighting, turf, scoreboards, parking lots, sidewalks, and playgrounds, reflecting the poor condition of many schools’ basic infrastructure. Notably, Mississippi’s statewide spending on building improvements and facilities exceeds combined ESSER investments in academics and student supports ($310 million). (See graphic for details)

For Mississippians, the substantial spending on facilities comes as no surprise, given the state’s long struggle to address infrastructural deficits. “Historically, Mississippi hasn’t funded facilities, so districts have to take out bonds for upgrades and improvements,” says Rachel Canter, executive director of the nonpartisan education policy and advocacy organization Mississippi First. But it’s hard for the state’s poorest school districts to issue bonds successfully. “As a result,” Canter says, “Covid money provided an immediate and easy facility fund…They may have done building improvements because they can’t raise bond money for those things or because the need is just so deep that they are using whatever dollars they can.”

Cleveland Public Schools, situated in the heart of the Mississippi Delta, one of the state’s most impoverished regions, has spent nearly $9 million, some 80 percent of its total ESSER spending to date, on essential roof and HVAC replacements at both a middle and high school. “All of our facilities are old. We don’t have a bonding capacity that is large enough to build new schools or make necessary improvements,” notes Lisa Bramuchi, the superintendent of Cleveland Public Schools. “Even with ESSER funding, it wasn’t enough to make major improvements that are needed.”

In Clarksdale Municipal School District, also in the Delta, outdated HVAC and roofing systems have led to significant repair costs over the years. To help stabilize its budget, the district is modernizing its facilities through the Clarksdale ONE Vision project, funded in part by substantial ESSER investments. Projects include HVAC upgrades, new, more energy efficient doors and windows, building automations, and other modernizations designed to generate future savings for reinvestment. As of March 2024, Clarksdale has invested roughly $16 million, about 80 percent, of its ESSER III funds into building improvements.

In the eastern part of the state, Neshoba County School District, serving students from the city of Philadelphia, is one of the few districts putting substantial dollars toward new construction projects. To date, the district has invested more than $12.3 million, or just under 90 percent of its spending so far, on building improvements and construction. The district is building a new physical-education gym along with two additional classrooms for its middle school, as well as undertaking a three-phase renovation project involving the installation of new HVAC units, renovations to bathrooms, and the replacement of windows and exterior doors in multiple buildings. “It would have taken us 20 or so years from a cost perspective to get all the projects completed without those funds,” former Superintendent Lundy Brantley said in a press release.

FutureEd’s analysis confirms how motivated poorer districts were to invest in infrastructure. Districts with the highest poverty levels in Mississippi are not only more likely to invest in facilities but also to allocate substantially larger shares of their ESSER III funds toward such projects. These districts are directing over half of their spending toward maintenance and facilities—more than twice the proportion allocated by the lowest-poverty districts. Specifically, 48 percent of their total expenditure has been dedicated to building improvements (HVAC, bathroom, roof upgrades), in stark contrast to the 17 percent allocated by their lower-poverty counterparts. Additionally, the highest-poverty districts are disproportionately investing more per pupil in building improvements ($1,563 vs. $295), underscoring their need to address infrastructure shortcomings.1

Research Insights

Though it might seem counterintuitive to focus on facility repairs when students need instructional support, research underscores the role of school facilities in shaping student achievement and well-being. Well-maintained and adequately equipped school environments positively influence students’ academic performance and motivation, while inadequate facilities contribute to absenteeism, health issues, and diminished cognitive abilities.

Studies have highlighted the connection between school environment and student absenteeism, which is particularly important for students with asthma. A 2017 study connects particulate air pollution to chronic absenteeism, while a 2013 study finds that updating classroom ventilation systems could reduce illness-related absences by 3.4 percent.

Research also links physical environment to academic performance. A 2015 study finds a positive correlation between improved ventilation, decreased classroom temperatures, and carbon dioxide levels, and a significant improvement in math scores. In the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), a 2017 study found that students attending newly constructed schools experienced notable improvements in standardized test scores, attendance rates, and teacher-reported student effort. After four years in the new buildings, the achievement gap between LAUSD students’ scores and the state average narrowed by nearly half in math and nearly 20 percent in English. And a 2023 study found that authorizing new school bonds for projects such as HVAC systems or roof replacements raised student test scores, particularly for students in poverty and students of color.

Beyond ESSER

Investing one-time ESSER monies in infrastructure could aid the future financial stability of Mississippi school districts as well as help them avoid falling off a fiscal cliff when the federal pandemic-response funds run out. Mary Filardo of the 21st Century School Fund points out that “schools in very poor condition are a drain on your operating budget. When an emergency comes up, you have to deal with it whether you have the money or not…So, if you took ESSER money to fix up your buildings, you could actually be relieving some pressure on your operating budget, which would be there for teacher salaries and for books and other kinds of student supports.” Additionally, Filardo says, poor building conditions exacerbate challenges in attracting and retaining staff, another significant expenditure for school districts.

Although Mississippi districts have about 40 percent of their ESSER III funds still available, the large investments in facilities suggest that a considerable portion of the funds may already be earmarked for such projects, i.e., under contract but not yet spent. Supply chain disruptions and labor shortages during the pandemic led to construction delays across the country, one of the reasons the federal government strongly discouraged districts from taking on comprehensive renovations and new construction within ESSER’s relatively short time frame. Districts that receive “liquidation extensions” from the U.S. Department of Education have until spring 2026 to spend out their ESSER monies.

The significant investment in facilities in Mississippi comes at the expense of funding for academic programs such as tutoring and summer learning opportunities—investments that many would argue were the intended focus of the funds. But the decision of many Mississippi school districts to invest heavily in school infrastructure reflects a pressing need with important implications for students in many of the nation’s schools—and a significant source of inequity in public education.

[1] District poverty levels were determined based on the number of 5- to 17-year old children in families living below the national poverty line, estimated through the Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) program of the U.S. Census Bureau. For this analysis, the “highest poverty” districts were defined as the 25 percent of regular school districts in Mississippi with the highest SAIPE estimates. The “lowest poverty” districts were defined as the 25 percent of school districts with the lowest SAIPE estimates.