Much has been written about how the academic and social disruption from the coronavirus outbreak is all but certain to disproportionately affect students from disadvantaged groups. But another important distinction that has received little attention is the impact on students at different ages.

A look at data from one Midwestern school district suggest that middle and high school students are struggling far more than their counterparts in 5th and 6th grades to navigate remote learning. And the older students are more likely to feel they don’t get the support they need from school or at home.

The results suggest some potentially large and troubling gaps in how students at different levels are experiencing the crisis. And while they represent the experiences of just one district’s students, they point to an important element that schools should consider when they reopen.

It’s not obvious at first who would be most affected in the shift to remote learning. Younger children are at an important developmental stage where the learning lost from COVID may be harder to make up later on; on the other hand, their parents may be able to make up more of the lost teaching. Older children may be disproportionately affected by the social isolation that comes with COVID, missing their friends and the support structures that K-12 schools offer.

I studied district-wide survey data from the medium-sized school district with about 4,000 students to investigate the grade-level differences in students’ early COVID experiences. The data, which come from Tripod Education Partners, also include surveys of parents and teachers. All told, more than 1,000 students from grades 5 to 12 completed the surveys, alongside over 1,000 parents and more than three-quarters of the district’s teachers.

The major finding is this: Middle school (grades 7-8) and high school (grades 9-12) students report sharp increases from their pre-COVID educational experiences in the difficulty with which they’re able to learn, while elementary students (grades 5-6) do not. Students were asked how difficult it was for them to learn both before and after COVID on a scale from 1 (learning is almost always hard) to 4 (learning is almost always easy).

Before COVID, students at all three grade spans reported it was somewhat easy, with means of 3.07 to 3.14. After COVID, elementary student means were almost exactly the same at 3.05, but the middle school students rating fell to 2.55 and high school to 2.36.

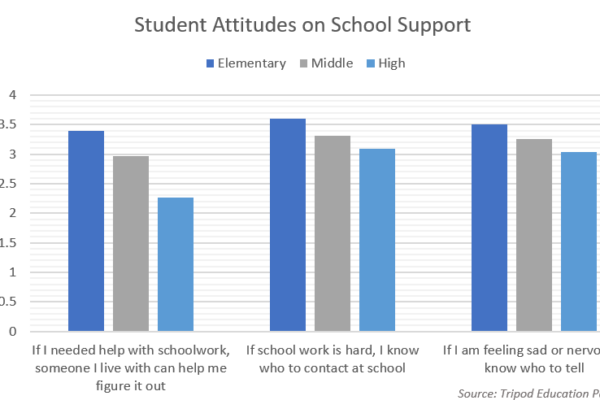

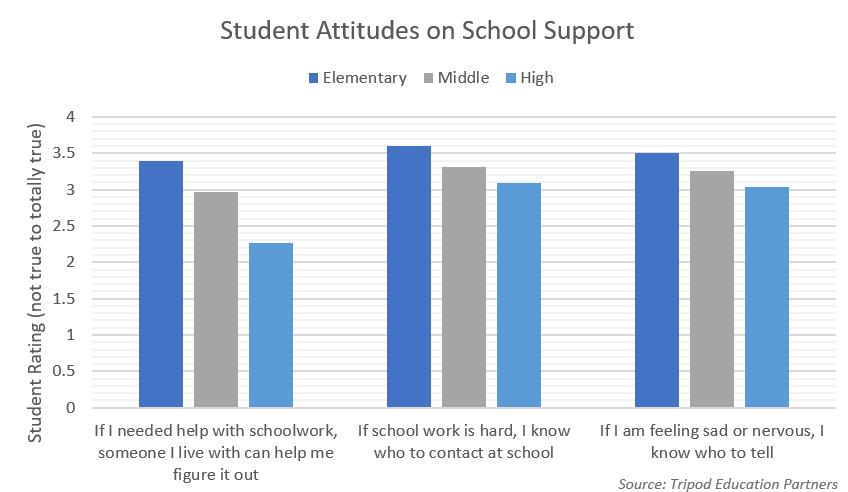

Why are students from different grades experiencing this crisis so differently? Other data from students, parents, and teachers in the district offer some clues. Student responses indicate that middle and high schoolers just aren’t getting the support they need from either home or school.

Elementary students report much more support from home and school on schoolwork.The younger students also report that they would know who to tell if they were feeling sad or nervous, suggesting they have the emotional support they need in this time. Interestingly, elementary students also reported on the survey that they are doing a little less schoolwork on average during COVID, while middle and high school students reported that they were doing about the same amount.

Parent reports back up what students are saying. Those with elementary students report much greater satisfaction with their communication with their children’s teachers, information on how to help their children learn at home, and the instructions their children receive about what schoolwork to do. For instance, parents of elementary students report an average satisfaction of 3.6 on a four-point scale with their communication with their children’s teachers, while parents of middle and high school students averaged 3.07 and 3.01, respectively.

[Read More: The Dos and Don’ts of Distance Learning in a Pandemic]

Though the differences in teacher survey responses were not as sharp, we also saw inklings of school policies and practices that may be contributing to these disparities. For instance, elementary teachers were more likely to say they had the tools and resources they need to be successful (a mean of about 4 on a five-point scale) than middle school (3.7) or high school (3.9). And high school teachers were slightly less likely to report that they were participating in online groups to share best practices than middle or elementary teachers.

Student responses to open-ended questions put an exclamation point on these findings. Elementary students were most likely to say they missed their teachers and their friends, with very few comments about the schoolwork or their own wellbeing.

Middle and high school responses were different. Middle schoolers were most often to report that they were getting too much work to do and commented on the lack of coordination among teachers and the difficulty of meeting multiple deadlines at once.

At the high school level, a common refrain was the difficulty of balancing school work with childcare responsibilities for younger sibling or their own children. Some of those surveyed expressed concerns about mental health, missing friends and the lack of focus without a firm schedule.

In general, high school students were far more likely to express negative sentiments on these questions than middle schoolers, who were far more likely than elementary students.

Educators and parents have so much to pay attention to that these issues may seem modest in importance. But the data in this district suggest that there are large and serious grade-level differences in how students are experiencing COVID.

As schools and districts prepare to educate students in what’s likely to be a tumultuous school year, they need to be sure those plans work for students of all ages. Otherwise, grade-level gaps may only grow.

Polikoff, a FutureEd senior fellow, is an associate professor of education at the USC Rossier School of Education.