Students in the nation’s wealthiest school districts have greater access to hybrid instructional approaches, which experts say provide students with the safest in-person educational experiences, than their peers at the other end of the resource spectrum, a FutureEd analysis shows.

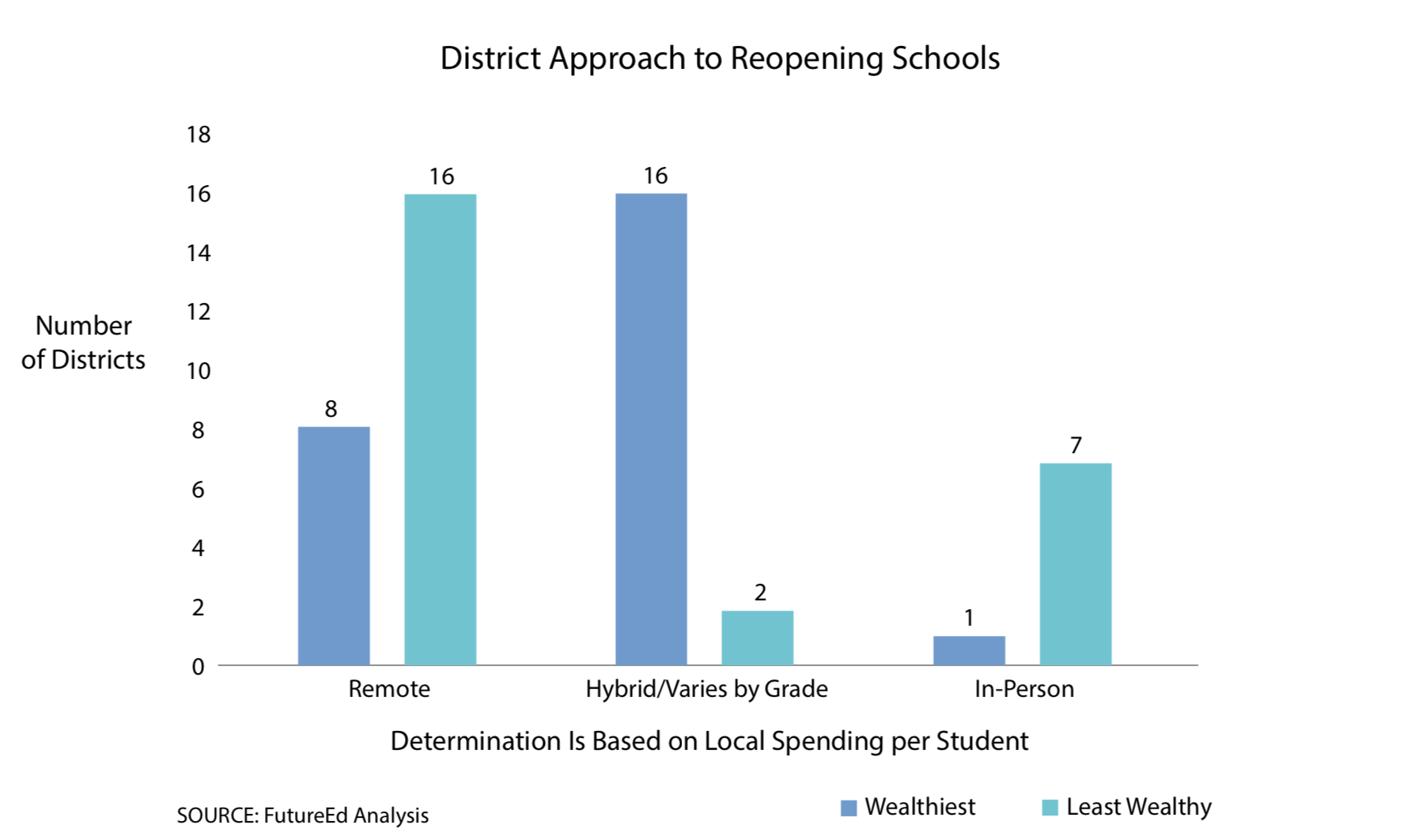

In comparing the nation’s 25 poorest and 25 wealthiest school districts, FutureEd found that 16 of the 25 wealthy school districts have some sort of hybrid schedule, either with all of the stude nts in class some of the time, or with some of the students, especially younger children, in class all of the time—instructional models that are more expensive and logistically challenging than in-person or virtual models. Only one has reopened fully, and eight are teaching remotely.

nts in class some of the time, or with some of the students, especially younger children, in class all of the time—instructional models that are more expensive and logistically challenging than in-person or virtual models. Only one has reopened fully, and eight are teaching remotely.

By contrast, 16 of the poorest districts are fully remote, seven are fully in person, and only two are using hybrid models.

The study included the 25 districts in the country with the lowest local revenue levels per student and the 25 districts with the highest local revenue levels as listed in a data set compiled by the School Funding Fairness Data System at Rutgers University’s Education Law Center. That revenue stream includes local property tax revenue and other local dollars.

Both sets of districts are small. Only 11 of the 50 enroll more than 4,000 students. And only one, the statewide district of Hawaii, has more than 10,000. The districts are geographically diverse, drawn from 16 states, though many of the wealthy districts are in New York state.

Five districts—three of the wealthiest and two of the least wealthy—chose a hybrid model for all students, with a portion of the students in person and half the students remote on the next day. Another 13 districts, all of them wealthy, brought back students in some grades only.

In six districts, elementary students attend school in-person every day, while older students remain in remote classrooms. Another three districts brought back elementary and middle school students, leaving high schoolers online. Some had in-person classes for elementary students and hybrid schedules for others.

Bringing younger children back to school first has several advantages. They are often the students who most need the in-person instruction and the socialization that schools provide. They are the students who can’t be left home alone. And some research suggests they are less likely to contract and transmit the coronavirus.

One reason for many wealthier districts adopting hybrid models could be the cost and logistics of safely executing hybrid instruction. Such things as teacher and student scheduling and bus routes are more complicated and more expensive under hybrid systems. “Hybrid models are typically more complex and resource-intensive to implement than either in-person or remote models,” David Rosenberg, a partner at Education Resource Strategies, has written.

The added costs of in-person instruction during the pandemic—including protective gear for students and teachers and daily disinfection of buildings and classrooms—compounds the problem.

[Read More: Key Questions to Answer About Reopening Schools]

Together with fresh budget cuts necessitated by a slowing economy during the pandemic, these challenges leave school districts with less revenue little choice but to offer only remote learning—even if many of their students lack computers and other equipment required for effective distance learning.

That’s what the majority of poorer districts in our analysis did.

Other researchers have found a similar trend. An analysis Michigan Department of Education data by Michigan State researchers, for example, found that students from low income districts in Michigan were significantly less likely to have an in-person learning option this fall than students from wealthier districts.

The long-term impact on students could be substantial. Districts nationwide have reported that students in remote learning options are struggling, including failing classes at a rate much higher than pre-pandemic, while learning loss has been dramatic among low-income students learning online in school systems that have made substantial achievement gains in recent years, including the District of Columbia Public Schools.

The divide between students learning remotely and those learning in person has emerged as a troubling new contributor to the already wide opportunity gaps in the nation’s schools.

Catherine Dragone is a FutureEd research associate.