Updated 1/19/2024

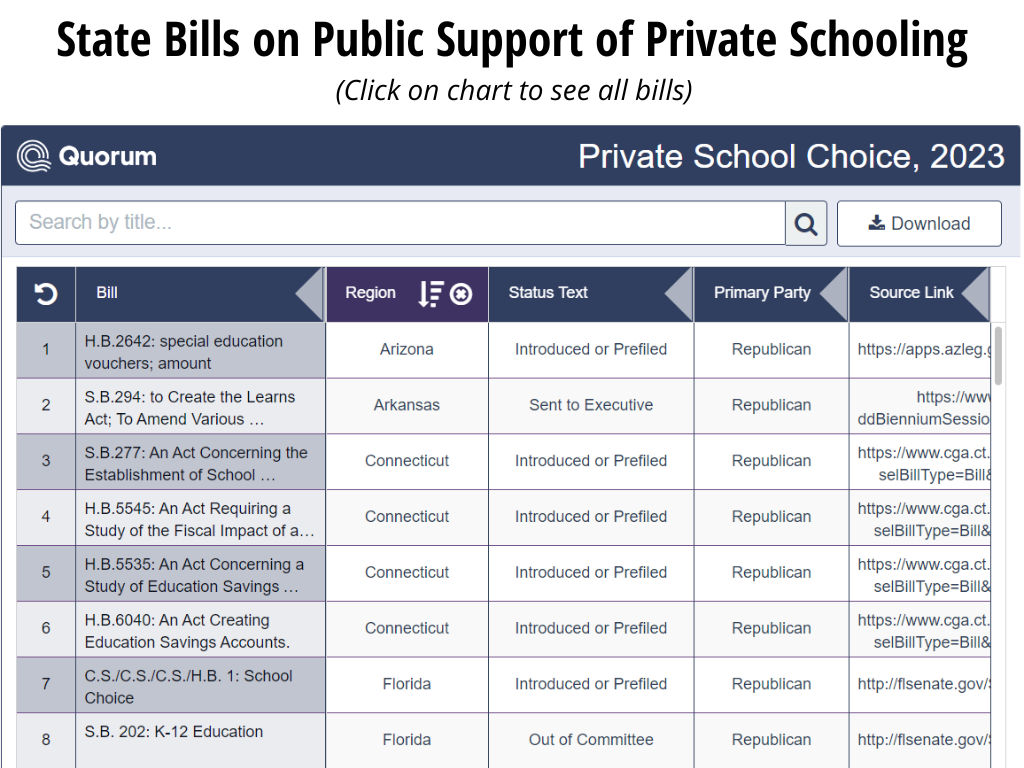

In the wake of Covid-19 and parents’ frustrations over school closings, mask mandates, and “culture war” curricula, public funding of private schooling has risen to the top of many states’ education agendas. In 2023, Republican lawmakers in at least 42 states proposed legislation to create or expand tax-funded programs to help parents cover the cost of private education.

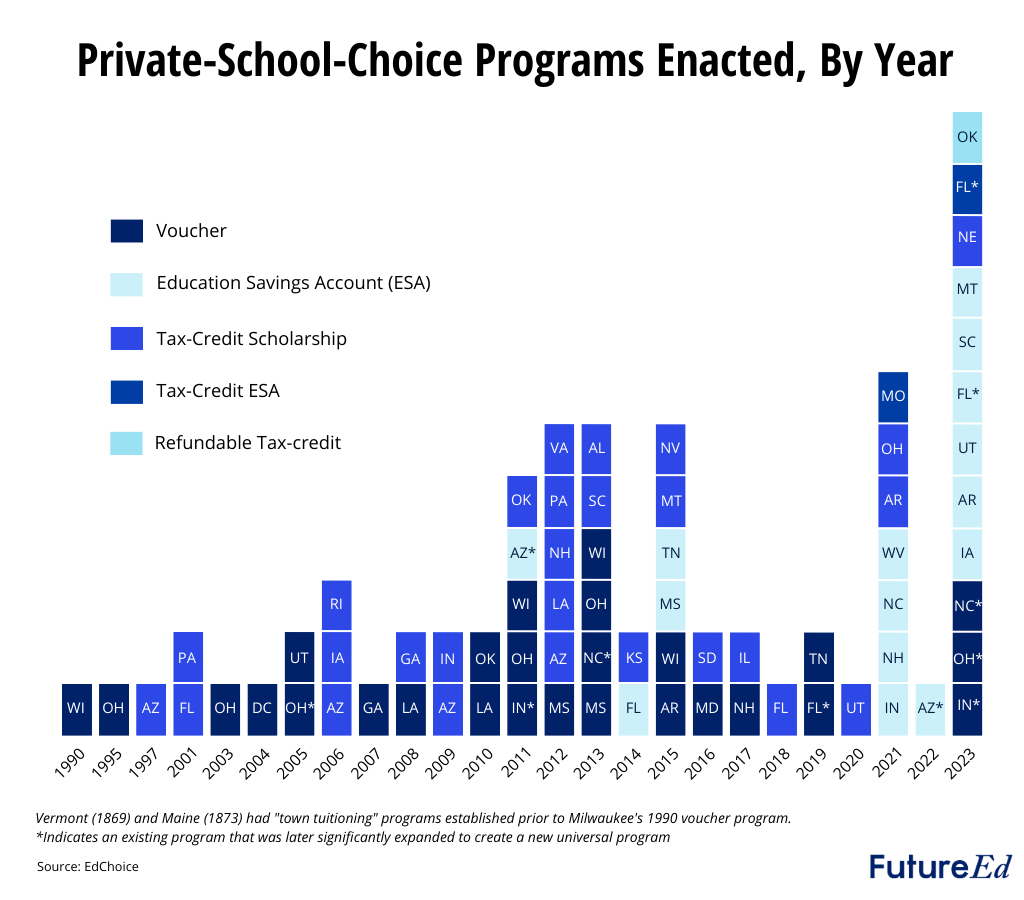

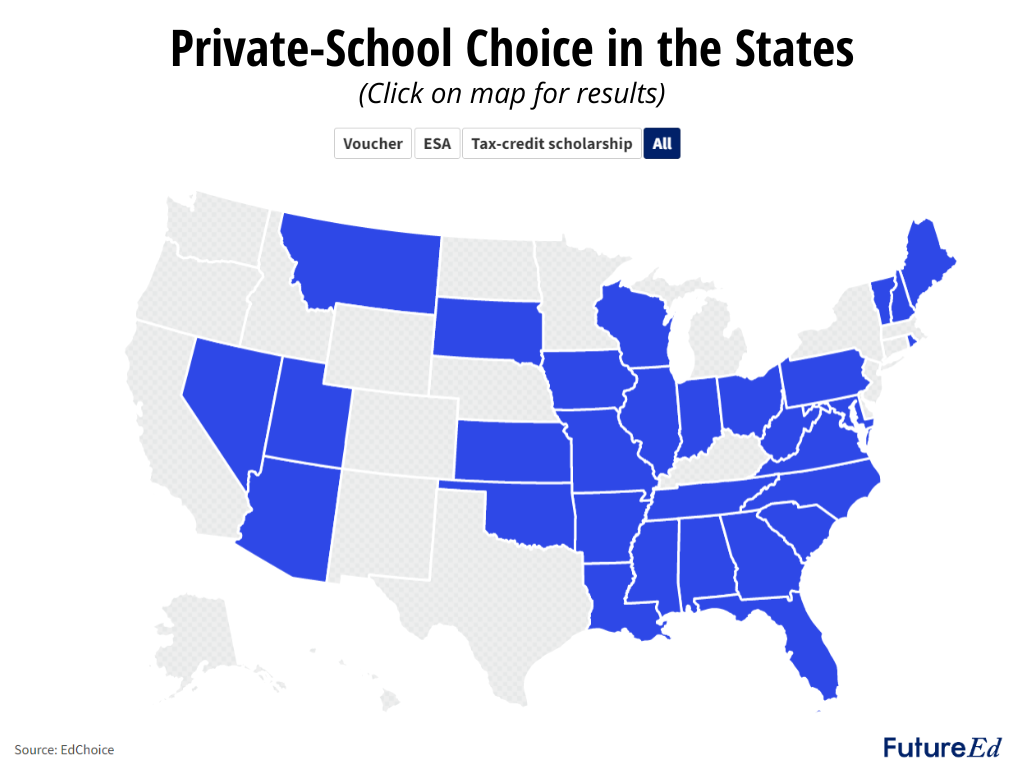

The modern private-school-choice movement began three decades ago in Milwaukee, when the state of Wisconsin began using public funds to pay for the cost of children from low-income families to attend, at no charge, private schools within Milwaukee’s city limits. Subsequent programs in other states also provided educational choices beyond public schools to primarily low-income students or students with disabilities. Currently, 32 states provide an estimated $6.2 billion in subsidies to some 982,000 students through tuition vouchers, education savings accounts, and tax-credit scholarships.

But many of the new and emerging private-school-choice programs emphasize empowering parents to choose their children’s school, rather than focusing on opportunities for families in need. New or expanded programs in 10 states—Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Indiana, Iowa, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Ohio, Utah, and West Virginia—are or soon will be open to any child in the state, regardless of financial means or disability status.

Some of the new programs, like Arizona’s, do not require students to have previously attended public schools. And some lack reporting requirements that would provide parents, policymakers and taxpayers insights into the quality of private-school options and whether private schools are helping students academically.

To help inform the national conversation about these recent moves, FutureEd has reexamined the research on private school choice, identified every major private school choice program nationwide, analyzed the trends they reflect, and sought to answer key questions about the programs, including whom they serve and their impact on student achievement.

What are the different types of private-school choice?

States use three major approaches to subsidize private-school tuition and other costs:

● Vouchers, the most widely known of the three, provide parents with some portion of their child’s state education funding in the form of a “coupon” to pay for tuition at a private school.

● Education savings accounts (ESAs) operate somewhat similarly, allowing parents to withdraw state funds deposited into individual accounts to pay for private school tuition, online learning, tutoring programs, or other approved educational expenses. The new, high-profile choice initiatives in Arizona, Arkansas, Iowa, and Utah are ESAs.

● Tax-credit scholarships allow taxpayers, both individuals and businesses, to receive tax credits when they donate to nonprofit organizations that provide private school scholarships.

Two states—Florida and Missouri—have recently launched a new type of program, Tax-Credit Education Savings Accounts, which function like ESAs but are funded through tax-credits received by donating to nonprofit organizations that fund and manage education savings accounts. Florida’s existing tax-credit scholarship program, originally enacted in 2001, was converted into a universal tax-credit ESA in 2023.

In addition to these programs, the tax bill Congress approved in 2017 allows parents to use 529 plans, tax-free savings accounts originally designated to fund college education, to pay for private school tuition. And some states offer other individual tax credits and deductions that allow parents to receive tax relief for approved educational expenses, including private school tuition. Oklahoma’s newly enacted universal program falls under this category, where parents can receive refundable tax credits to cover educational expenses.

Whom do these programs serve?

The number of students receiving vouchers, ESAs, and tax-credit scholarships has expanded since the advent of the Milwaukee voucher program in 1990, especially in the past decade. In the current school year (2023-24) about 982,000 students are enrolled in private schools or accessing other private educational opportunities through one of the three programs. Among these, ESAs currently have the highest student enrollment and show the most significant growth, with more than 326,400 students taking advantage of the public funds at the start of the 2023-24 school year. An additional nearly 126,000 students are using Florida’s tax-credit ESA, which functions like a traditional ESA. By comparison, an estimated 49 million students attend public schools.

Some supporters of private-school-tuition programs argue that including more—and more affluent—students in private-school-tuition programs would increase the supply of private schools and give students a wider range of educational options. But it’s not clear whether the supply of private-school seats and the number of new private-school attendees can be expected to increase as participation in the programs expands.

One significant barrier to increased supply is that it’s hard to start new schools, particularly good ones. In Indiana, the number of students in private schools has not changed substantially since the 2014-15 school year, shortly after the state’s voucher program was opened up to moderate-income students and to those who had never attended public school. But the share of private school students receiving state vouchers to offset their tuition has climbed from 34 percent to 52 percent, state data show. That is, more than half the state’s private school seats are now publicly funded.

When Arizona’s ESA program expanded to become universal in September 2022, the state department of education estimated that 75 percent of the roughly 7,000 initial applicants in the universal category never attended an Arizona public school. While some of the applicants entered private schools in kindergarten, they likely account for a modest portion of the applicants. Homeschooled students may also participate in the Arizona ESA program, using the money for such expenses as curriculum materials and tutoring. In Arkansas’ new ESA program, 31 percent of the initial 5,000 participating students are entering kindergarten for the first time and 64 percent were already enrolled in private school.

In some places, new schools have launched to serve students receiving vouchers, but research suggests they don’t always last long. A 2016 study of Milwaukee’s voucher program found that 41 percent of the 247 schools serving voucher students between 1991 and 2015 shut down. Start-up schools accounted for 80 percent of the closures.

Students with disabilities

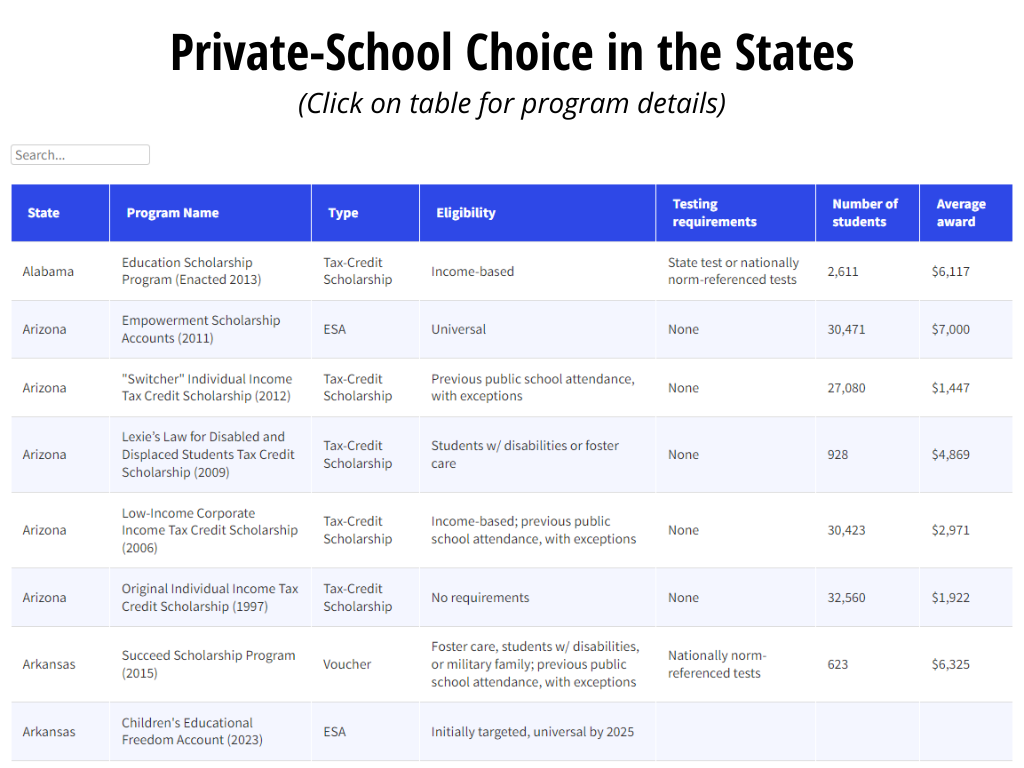

About a third of the nearly 70 existing voucher, ESA, and tax-credit scholarship programs are specifically for students with disabilities, such as Georgia’s Special Needs Scholarship voucher program and Mississippi’s voucher programs for students with speech-language impairments or dyslexia. These programs are typically open to all children with a diagnosed disability or proof of an individualized education plan (IEP), regardless of family income. Sometimes these programs require a student to attend public school or be zoned to an underperforming public school prior to receiving the voucher.

The recent movement toward universal programs is leading some states to expand these specialized programs to include the general student population. Arizona’s education savings account initiative—Empowerment Scholarship Accounts—while originally intended for students with disabilities, or those attending public schools with a D or F rating, recently expanded to include all families.

Income requirements

Most older programs assisting with private-school tuition set income-eligibility requirements that vary from state to state and across programs. Families in Washington, D.C., for example, are eligible to receive a voucher if they make less than 185 percent of the federal poverty line ($55,000 for a four-person family in 2023-24). That’s the benchmark to qualify for the federal Free and Reduced-Price Lunch program, an often-used proxy for low-income status. Once students receive a voucher, families remain eligible at 300 percent of the federal poverty line—the eligibility level of many states’ programs. Some programs don’t have income requirements but reserve a certain number of scholarships for low-income families or give those families priority.

But in some states, those older income limits are expanding. Indiana’s voucher program, launched in 2011, is now open to any child whose family makes less than 400 percent of the amount required to qualify for the federal free and reduced-price lunch program, about $220,000 for a family of four in 2023-24. At that threshold, 98 percent of Indiana families are eligible.

And the newest private-school choice programs are designed to be or soon become universal. Iowa, for example, approved a universal ESA program in January 2023 that provides nearly $8,000 in state funding—the same amount the state provides for students in public school–for each family who chooses to send their child to a private school. The program initially focuses on low-income families, but within three years, all families will be able to participate. Arkansas Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders recently signed into a law a similar measure with its Education Freedom Account, which would first serve at-risk families, and then all families in three years. Utah’s new ESA program, which is set to begin in 2024-25 school year, will be immediately accessible to all students.

Some 2023 proposals to expand eligibility under existing programs failed, including proposals to expand the Missouri Empowerment Scholarship Accounts Program, MOScholars. Established in 2021, it currently serves students with an IEP or from families making less than 200 percent of the threshold to qualify for FRPL ($111,000 for a family of four in 2023-24). But proponents across states are expected to introduce expansion proposals again in the 2024 legislative sessions.

Previous public-school attendance

Many proponents of the Milwaukee voucher program and other early private-school-choice initiatives promoted them on the grounds that they would provide options to students in under-performing public schools. Some programs, as a result, require previous public-school attendance. Arizona’s “Switcher” tax-credit scholarship program, launched in 2012, requires 90 days of attendance in public schools. Children are eligible for Georgia’s tax-credit scholarship program if they attended a public school for at least six weeks immediately before receiving a scholarship.

Some states combine public school attendance with other eligibility requirements. Arkansas’s voucher program, Succeed Scholarship Program, launched in 2016, requires that students have attended public school for at least one full year before they are eligible for a voucher and they must be in foster care or have a disability or an Individualized Education Plan (IEP). Florida’s Hope Scholarship tax-credit program for students who have attended a public school for at least one year and experienced bullying or violence at that school. Others require the student to have attended or be zoned to an underperforming school.

Several states permit students attending school for the first time to enroll directly in private schools using public funding. Georgia’s tax-credit scholarship program, for example, exempts prekindergarten, kindergarten, or first-grade students from its six-week, public-school-attendance requirement.

Others, like Alabama, have no public-school-attendance requirement but reserve 75 percent of its scholarships for new private-school attendees. Dependents of military members are often exempt from public-school-attendance requirements, as are siblings of scholarship recipients.

Sparsely populated Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont have unique “tuition town” voucher programs that allow students in school districts lacking grade levels to use tuition vouchers to attend schools in other districts.

But a growing number of private-school-tuition programs serve many students who have never attended public schools. That’s true for 74 percent of students in the 10-year-old Wisconsin Parent Choice Program in 2022-23 and 73 percent of student in New Hampshire’s two-year-old Education Freedom Account. In Indiana, only 4,412 of the 44,376 students in the state’s 2021-22 choice scholarship program had spent at least two semesters in public school.

But a growing number of private-school-tuition programs serve many students who have never attended public schools. That’s true for 74 percent of students in the 10-year-old Wisconsin Parent Choice Program in 2022-23 and 73 percent of student in New Hampshire’s two-year-old Education Freedom Account. In Indiana, only 4,412 of the 44,376 students in the state’s 2021-22 choice scholarship program had spent at least two semesters in public school.

What do we know about student outcomes in private-school choice programs?

The research on school vouchers and other private-school-choice programs is mixed.

Early studies showed promising effects of smaller-scale programs. A 1999 study of Milwaukee’s voucher program found that after four years of participation in the program, voucher students scored nearly 11 percentile points higher than control students in math and about six percentile points higher in reading. A 2002 study of voucher programs in Dayton, New York City, and Washington, D.C., found gains for Black students on the Iowa Test of Basic Skills. And a 2021 meta-analysis of 21 earlier studies representing 11 school-choice programs in both the United States and abroad found statistically significant positive effects on academic achievement, particularly in reading.

A 2019 study of Florida’s Tax Credit scholarship program found that students attending private schools on vouchers were 12 to 19 percent more likely to attend college and up to 20 percent more likely to graduate than those who remained in the public school system.

But a majority of recent studies of statewide programs have found negative academic results.

A 2018 study of Indiana’s Choice Scholarship Program found that low-income students who attended private schools on vouchers saw losses in math achievement, compared to similar students in public schools. A 2019 study of the Louisiana Scholarship Program found that after four years, students continued to experience sustained large negative effects on academic achievement, particularly in math. A 2016 study of Ohio’s Educational Choice Scholarship program also found lower test scores among scholarship recipients compared to their matched peers.

A 2019 study of D.C.’s voucher program found that three years into the program students performed on par with the city’s public-school students, after voucher recipients underperformed their public-school peers in the first and second year of participation. The 2019 study found positive effects on student satisfaction and feelings of safety among voucher students, as well as lower levels of student chronic absenteeism. But parent satisfaction was no higher than that of parents’ whose children did not receive a scholarship. Another study of the District of Columbia voucher program found that attending private schools with vouchers had no significant effect on college-going.

Why the earlier, smaller-scale tuition programs showed more promising academic results is not clear. It’s possible that as the programs expanded to include more students, there weren’t enough high-quality private schools to respond to the growing demand. It’s also possible that the curriculum at private schools does not align with what’s measured on standardized tests.

Are there accountability measures in the programs?

Charter schools—publicly funded but privately operated schools that provide another type of school choice to some 3.7 million students—are responsible to the public and public authorities in several ways. They are not allowed to set admissions standards (though some shape their enrollments in different ways). They must go through an authorizing process that evaluates their academic and financial strength before they’re allowed to open their doors. And they must abide by state and federal accountability programs, administering the same standardized tests that students in traditional public schools take

But private-school-tuition programs vary widely in the degree of transparency and accountability they require of private schools. Private schools are under no obligation to participate in the tuition programs and some don’t out of a desire to avoid public regulations. Schools that do participate may admit students selectively.

Some programs—including voucher systems in Indiana, Louisiana and Washington, D.C.—require that students take the same state standardized test as their public-school peers, allowing for comparisons among those using vouchers and those remaining in the public system.

Others, such as the voucher programs in Maryland and Arkansas, call for administering commercial tests, which allows for tracking students’ year-to-year progress but not for comparing results to those of students in local public and public charter schools, who under federal law must take state-administered standardized tests. Nor are most of the commercial tests aligned to state standards. In all, 18 of 24 voucher programs nationally require some sort of student testing. Most programs without testing requirements serve only students with disabilities.

Half of the voucher programs with testing requirements mandate the use of state tests, allowing comparisons between public and private school performance. A 2014 study of Milwaukee’s voucher program by researchers at the University of Arkansas and the University of Wisconsin-Madison found that adding a test-based accountability measure seemed to increase student achievement among voucher recipients.

Wisconsin has additional accountability measures. It requires that Milwaukee private schools accepting vouchers become accredited within three years of entering the program and comply with regulations aimed at measuring and strengthening academic quality, including reporting information about academic programming and student performance. Students must receive a minimum number of hours of direct instruction. Teachers must have at least a bachelor’s degree from an accredited higher education institution. And participating schools must submit a yearly financial audit and proof of financial sustainability, meet all non-discrimination policies and health and safety codes, and conduct background checks on employees.

Other accountability features in voucher programs include a requirement in North Carolina’s Opportunity Scholarships program that participating private schools must provide yearly reports to parents on their child’s academic progress. Schools must operate for at least one year prior to accepting vouchers under Arkansas’ Succeed Scholarship program. And schools in the District of Columbia’s Opportunity Scholarship program must allow campus visits.

In contrast, only three of the nation’s 15 ESA programs require participating students to take state standardized tests, including Iowa’s recently enacted universal program. Utah and Arizona’s new universal programs have no student performance reporting requirements. Ten of the 26 tax-credit scholarship programs require testing, including two that require state testing.

Democratic lawmakers in Florida, Iowa, Montana, and Tennessee introduced legislation in 2023 to increase transparency and accountability within their states’ choice programs. The Montana legislature considered two bills that would have required private schools that receive tax-credit scholarships to test students and make that information publicly available. Tennessee Democrats introduced companion bills that would have required private schools in choice programs to publish on their websites lesson plans and syllabi, a list of library materials, and the academic standards for each class offered. Neither bill passed.

in Florida, Iowa, Montana, and Tennessee introduced legislation in 2023 to increase transparency and accountability within their states’ choice programs. The Montana legislature considered two bills that would have required private schools that receive tax-credit scholarships to test students and make that information publicly available. Tennessee Democrats introduced companion bills that would have required private schools in choice programs to publish on their websites lesson plans and syllabi, a list of library materials, and the academic standards for each class offered. Neither bill passed.

Bills in Iowa would have required applicants to report information such as family income, race and ethnicity, and disability status, as well as limit eligibility for the new universal ESA program established in 2023 to families who make less than 400 percent of the federal poverty line. And a bill in Florida would have required private schools that participate in a choice program to administer the state test to scholarship students, establish a curriculum that meets state standards, and submit annually information on scholarship students’ graduation rates and test scores as well as the school’s budget.

In one of the first moves of the 2024 legislative season, Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs called for increasing transparency and accountability in the state’s existing universal ESA program, including a requirement that students attend public school for a minimum of 100 days before becoming eligible to receive funds.

The absence of test results, graduation rates and other publicly available information on school performance potentially undermines the theory of action behind private-school choice—that parents will pursue the best academic environment for their children. That is difficult to do without insights into the quality of the choices they have. Many supporters of public support for private schooling nonetheless oppose transparency and accountability in private-school-choice plans, even as they rightly advocate for accountability in public schooling and for transparency in state and local educational uses of federal Covid-recovery funding in the wake of the pandemic.

These seemingly contradictory stances raise significant questions about the goals and metrics of accountability. Is there a material difference between parents’ perception of a school’s quality and parents’ perceptions combined with objective evidence of student success? And who should be empowered to answer that question, parents or taxpayers?

Taxpayers, of course, have a stake in ensuring private schools are held accountable for the use of public dollars and many taxpayers don’t have children in school. Some commentators have criticized Arizona families for spending education savings account funds on trampolines and kayaks, though such investments could have educational value. But state officials have also found families buying beauty supplies with the funds and attempting to withdraw cash from their accounts under an ESA program for students with disabilities.

What is the impact on public schools?

Some evidence suggests that introducing vouchers spurs improvements in public schools by forcing them to compete with private schools. A 2020 National Bureau of Economic Research study found that the expansion of Florida’s tax-credit scholarship program resulted in higher standardized test scores and lower absenteeism and suspension rates for public-school students. Another 2020 study by the advocacy organization EdChoice, found no impact on the average public-school student from the Indiana choice program but found a small positive impact on low-income children.

Many worry about the impact of private-school choice on public-school funding. There’s research suggesting that private school choice programs don’t hurt public funding. For example, a 2021 study of Virginia’s tax-credit scholarship program estimates that the program saved the state $8.5 million by moving students from public to private schools.

Some programs limit the number of vouchers or scholarships that can be awarded each year. South Carolina’s newly enacted ESA program, for example, sets a cap at 5,000 students in year one (2024-25), 10,000 students in year two, and 15,000 students thereafter. Utah’s new universal ESA program is limited to 5,312 students due to the legislature’s appropriation of $42.5 million. (Arizona’s universal ESA program, on the other hand, has no cap on the number of participants, meaning that there is technically no limit on how much state funding can flow to private schools.)

Other programs cap funding outlays. Indiana’s voucher program limits funding for each student to 90 percent of the state’s public school per-pupil expenditure. Arkansas’ voucher program has a $7,413 cap. Both states’ average awards hover around 50 percent of state per-pupil spending. Ohio limits K-8 vouchers to $5,500 per student and high school vouchers to $7,500, and the average award is closer to 40 percent of state per-pupil funding. Louisiana’s 15-year-old voucher program caps awards at 100 percent of the state’s per-pupil expenditure for public schools, but the average voucher award is less than 70 percent of that threshold.

The recent expansion of the Arizona ESA program is instructive. In the 2022-23 school year, $304 million went toward the program, supporting roughly 67,000 students with awards ranging from an average of $7,000 to up to $43,000 for specific students with disabilities. Many of these students had never attended public school.

While that doesn’t necessarily mean a decrease in funding available to public schools since school districts never expected funding for students they never educated, it’s a burden Arizona’s taxpayers must bear. The governor’s office projects that the program will cost taxpayers more than $940 million in fiscal 2024—$320 million higher than the approved amount in the fiscal 2024 budget. Additionally, they also estimate that 50 percent of the funding constitutes a new expense to the state, attributed to the students previously enrolled in private schools or homeschooled. When the program was introduced by legislators in 2022, they initially estimated an additional state cost of $65 million by the second year of its implementation.

To help public school systems manage lower enrollments under its new ESA program, Iowa plans to partially offset the loss by providing them some funding for each student who enrolls in a private school. Even so, the state estimates Iowa will send about $107 million in state money to private schools in the 2023-24 school year, the program’s first year, and that the state subsidy will eventually reach $345 million annually.

Some argue that private-school-tuition subsidies can relieve the financial pressure on over-crowded or understaffed public-school districts. Arizona, for example, has several thousand teacher vacancies and other positions filled by long-term subs or teachers-in-training. Shifting more than 70,000 students to private school may help reduce demand for teachers. On the other hand, Arizona teacher salaries lag those of most states, and some argue that investing in pay raises would help address the shortage problem.

Why do parents choose to use vouchers, tuition-tax credits or ESAs?

Parents pursue private-school education for many reasons. In a study conducted on the experiences of parents and students in the first year of the District of Columbia Opportunity Scholarship Program, a voucher program that launched in the early 2000s, many parents said that their participation “was motivated by the belief that private schools have better discipline, higher academic standards, and less violence than public schools.”

In a recent poll conducted for EdChoice by Morning Consult, about half of parents in both public schools and private schools say that location is the primary reason they send their child to their current school. Yet 51 percent of private school parents cited safety as a primary reason, compared with 29 percent of public-school parents. The differing responses suggests that parents concerned about safety—whether because of bullying, school shootings, or other reasons—may be more likely to seek out private schools. Public-school parents may care equally about safety, but private schools are either financially or logistically not an option for them. Notably, the same poll found that about half of parents with school-age children in states with voucher or ESA policies are unaware of those choice programs available to them.

Pandemic-related school closures also seem to have increased parental appetite for school choice. This could be because parents saw that some private schools remained open during the pandemic or reopened more quickly than public schools, or because public school parents saw more of what education looks like during virtual learning and were displeased.

Why is private school choice controversial?

School choice, and particularly private-school choice, is often politically charged. Some see it as an attempt to undermine public education, others see it as a way to provide parents a greater role in the educational lives of their children and greater opportunities for students.

The debate is often framed as: Should public dollars fund private education? But the controversy over school choice also reflects a philosophical debate about the purpose and design of publicly funded education. Some believe that the system of public education should be the recipient of funds, a system whose function is to provide quality public education to all American children. Others contend that public funding should flow to the child and used for an education of the child’s (and the child’s family’s) choosing, whether in public or private schools.

For some, their student-centric perspective on education funding reflects a libertarian skepticism of government and government-provided services, including public education. Yet many who believe in the importance of sustaining a collectively-funded system of public education support giving students other options when their local public school underperforms.

That belief, together with efforts to desegregate the nation’s schools, led to the creation of more choice within public education: magnet schools, publicly funded but privately operated charter schools, and intra- and inter-district choice plans that let students attend different schools within their school districts or in neighboring districts. While religious schools have been barred in some places from receiving public funding because of the U.S. Constitution’s prohibition against government establishment of religion, recent U.S. Supreme Court rulings have opened the door to including religious schools in choice programs.

Many if not most parents in the United States look at the quality of local public schools when deciding where to live, and less-affluent families are often relegated to lower-performing schools in under-resourced neighborhoods. School-choice programs offer those families a wider range of educational opportunities. But the trend toward universal programs with few performance reporting requirements will seemingly make it more difficult for families to make informed choices for their children. And it raises the question of whether universal systems such as Arizona’s and Arkansas’ will result in relinquishing the long-standing emphasis on educational equity in school choice.