Summer has traditionally been a time when students lose some of the skills they gained during the school year, a phenomenon known as “summer slide” that is particularly common among children living in poverty. But this year and next, school districts across the country are planning to use the summer months to help students recover the instructional time they lost during the pandemic.

With districts and charters required to spend at least 20 percent of their federal Covid-relief aid on addressing learning loss, summer learning has emerged as the No. 1 strategy for academic recovery, measured by the number of school districts planning to invest in it and the amount of money designated for summer learning programs.

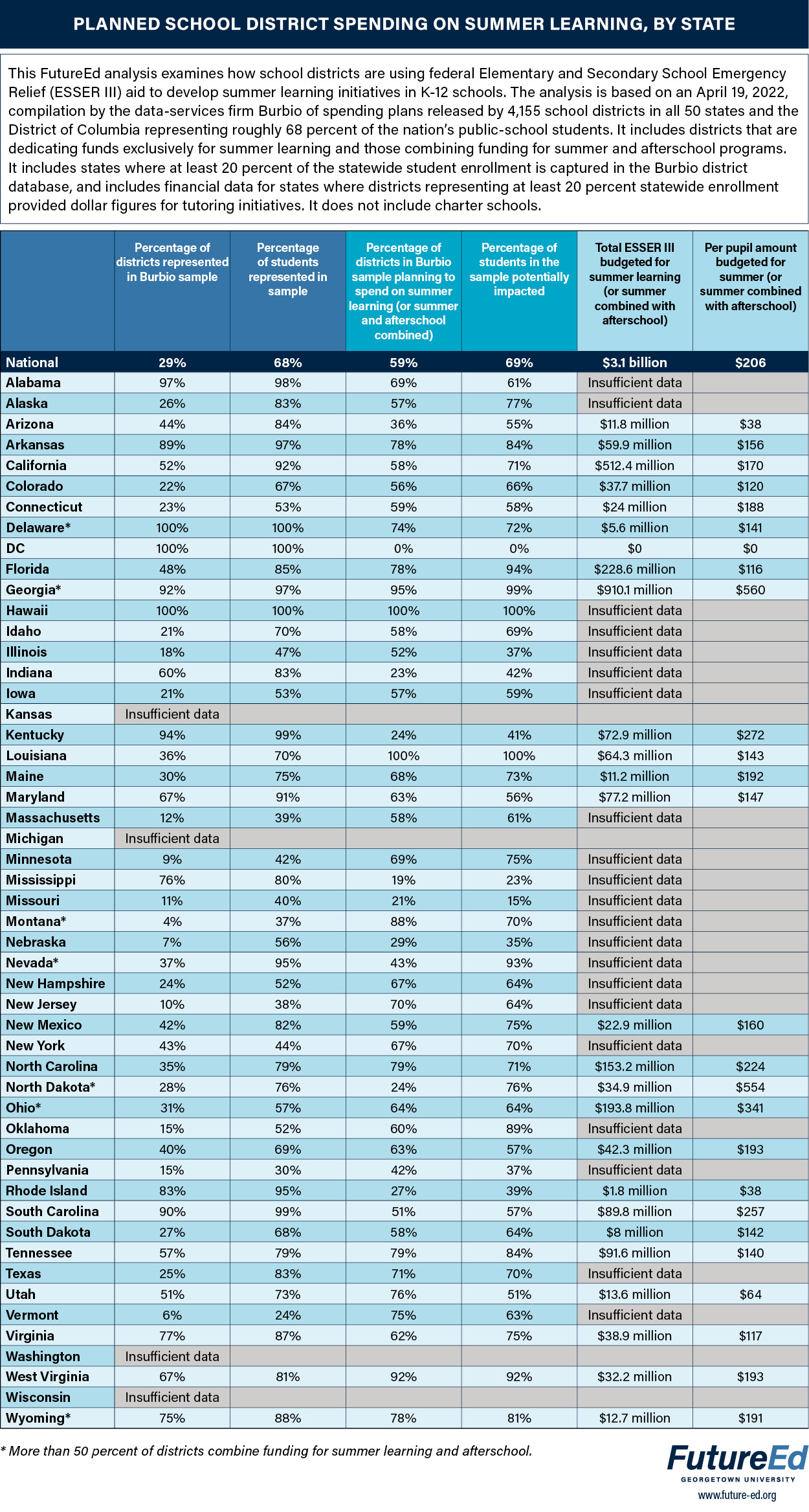

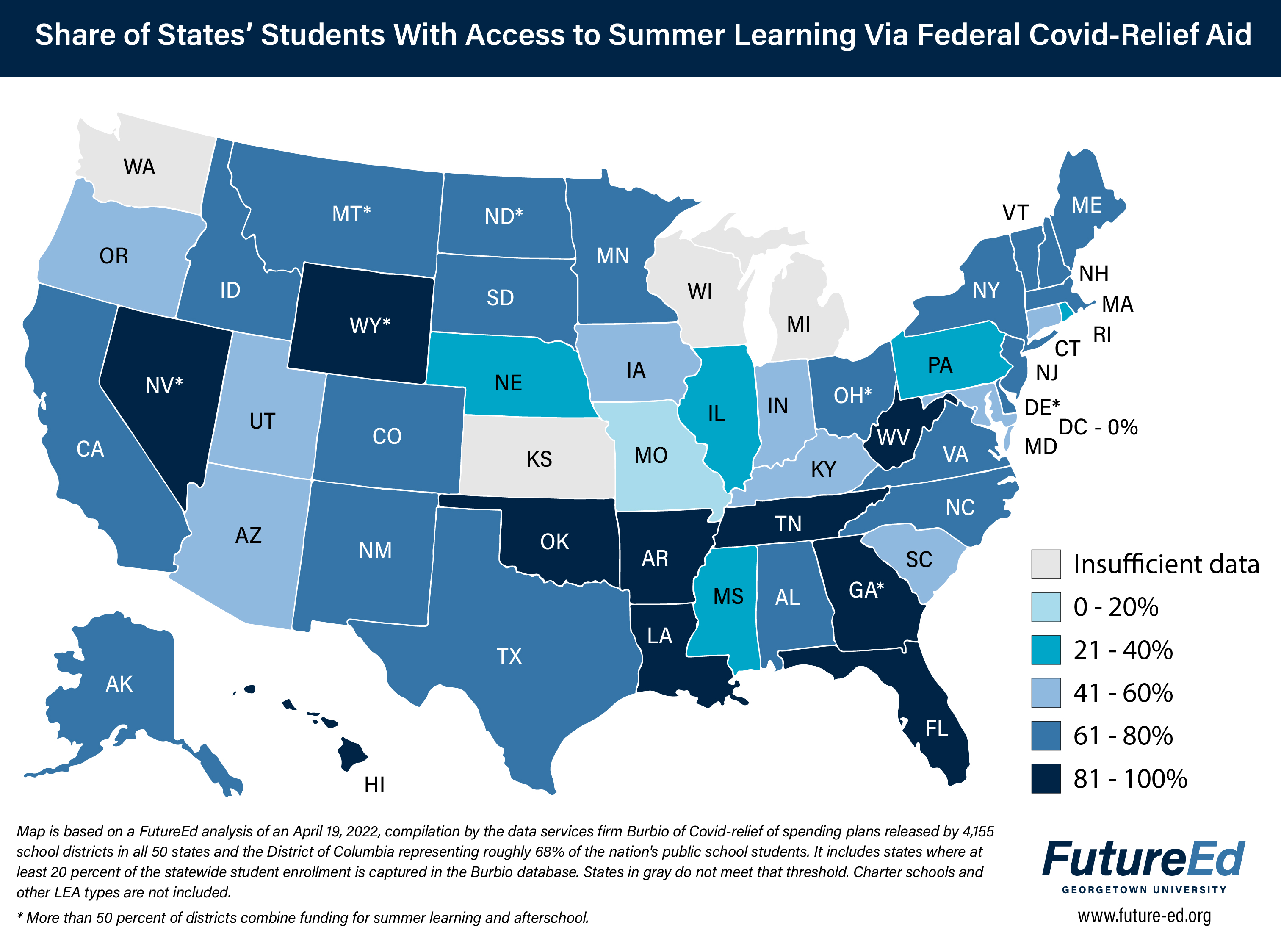

Nearly 60 percent of the nation’s school districts and charter organizations expect to spend a portion of their federal American Rescue Plan funding on summer learning or on a combination of summer and afterschool programs, according to a FutureEd analysis of spending plans for more than 4,100 local education agencies compiled by the Burbio data services firm.

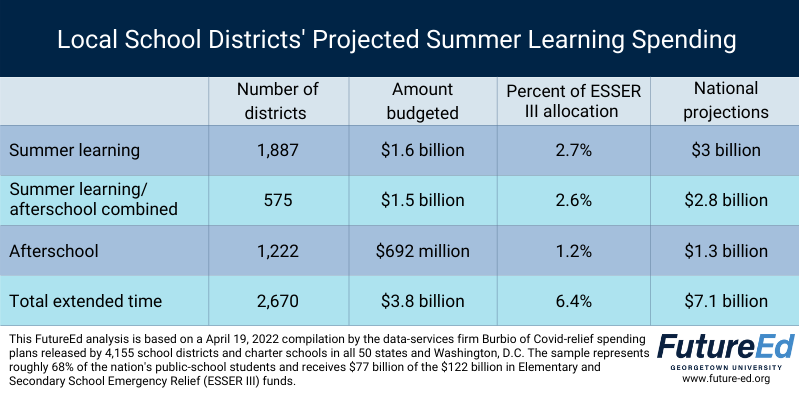

The proposed spending among districts and charters that provide dollar figures for these priorities adds up to about $3.1 billion so far. Since the Burbio sample is roughly nationally representative*, comprising 68 percent of the nation’s public-school students, it’s  possible to estimate that spending on summer learning or summer learning and afterschool programming combined could reach $5.8 billion nationwide under the latest round of Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER lll) by the time the federal aid must be fully committed in September 2024. When stand-alone afterschool spending is included in the calculation, the total for extended-time programs could reach $7.1 billion.

possible to estimate that spending on summer learning or summer learning and afterschool programming combined could reach $5.8 billion nationwide under the latest round of Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER lll) by the time the federal aid must be fully committed in September 2024. When stand-alone afterschool spending is included in the calculation, the total for extended-time programs could reach $7.1 billion.

In addition, state education agencies, which are required to spend at least 1 percent of their federal allotment on summer programs, or about $1.2 billion nationwide, are providing grants to supplement districts’ planned expenditures.

And philanthropy is contributing additional resources to help school districts provide more than traditional summer offerings. In New York City, for instance, Bloomberg Philanthropies has organized a $50 million Summer Boost NYC initiative to support summer learning for 25,000 students in the city’s charter schools. In Philadelphia, the William Penn Foundation is providing $4.6 million to 22 summer learning programs working with as many as 29,000 students. And the San Diego Foundation is partnering with San Diego Unified School District to provide $14 million in summer learning grants.

Research shows that well-designed summer programs lead to gains in reading and math and support the social-emotional development of students when students attend regularly. A study of several programs by the RAND Corporation suggests that the most effective summer programs run for at least five weeks, preferably six, and provide at least three hours a day of academic instruction—a standard few districts currently meet. Students who attend at least 80 percent of the summer classes and return in subsequent summers achieve the best results. Many successful programs combine academic with enrichment activities, often in partnership with community organizations.

While many school districts offered summer school opportunities pre-pandemic, a FutureEd study of the nation’s 100 largest districts’ ESSER III spending plans suggests that federal Covid-relief aid is intensifying academic-recovery efforts. Districts that assigned specific dollar figures to summer learning are planning to spend upwards of $773 million of their ESSER III money on summer learning, potentially impacting nearly 5.8 million students. Another $457 million could go toward summer learning in large districts that combine summer learning with afterschool investments in the spending plans, affecting another 700,000 students.

[Read More: An Analysis of Local Districts Ambitious Post-Covid Tutoring Plans]

Miami-Dade County Public Schools has budgeted $120 million over four summers, or 12 percent of its total American Rescue Plan allotment. The New York City Department of Education, the nation’s largest school district, designated $100 million for its six-week Summer Rising program in 2021, and city agencies are investing $101 million in the program this year. Many districts funded summer learning programs in 2020 and 2021 from earlier rounds of ESSER aid.

FutureEd’s analysis of district spending plans and websites identified trends in how large districts are using federal, state, and other resources on summer learning. They include:

- Four weeks is the most common length for summer programs, with at least 31 of the 100 largest districts setting their programs at that duration or at the one-month mark. Another 10 are offering five-week programs and eight provide six weeks of summer learning. The remaining districts range from two to 10 weeks or have not yet provided a time frame. Miami-Dade County, for example, offered a 10-week program in 179 school last summer, and the Cobb County, Georgia, public schools provided two-month programs for students who need extra support.

- Many of the programs go beyond traditional, academic-oriented summer school offerings to provide enrichment activities, arts, and social-emotional support for students. Schools in Orange County, Fla., are offering music enrichment and science acceleration, in addition to traditional credit recovery courses for high school students. Gwinnett County, Ga., has developed the Support + Enrichment + Acceleration (SEA) Program that aims to prepare students for the next grade level and fill any gaps in learning. The IDEA charter network in Texas is using its summer camp program to offer students science lessons set in nature, along with canoeing and swimming.

- While several of the largest districts open their summer programs to all students, many concentrate on the traditional summer school population: students at risk of having to repeat a grade. Chicago, San Diego and Hawaii (where students statewide are incorporated into a single school district) are supporting students in transition years: kindergarten, third, sixth and ninth grades. Louisville’s programs are located in neighborhoods where children of color comprise a large share of the community. Howard County, Md., is focusing on schools with high rates of poverty and lagging performance. Several districts are using their ESSER III money to offer programs free of charge.

- Some districts are supporting additional learning time in other ways, including investing their Covid-relief aid in extended-year programs that keep students in school for more of the calendar year. In Dallas, for instance, 41 schools are using what’s known as an intersession calendar, a 10-month calendar which runs from early August to late June with breaks during the school year. More than a third of the students in these schools, about 7,000, have been attending week-long, school-based “vacation academies” during the breaks. The academies average about 14 students each and contribute to gains in reading at campuses with intersessions, early results show. A 2020 field experiment by University of Virginia researchers found that students who attended the academies showed improvement in attendance and achievement. Dallas is investing up to $73 million of the federal aid in this approach. The Dallas district also offers summer learning but is not using ESSER III for those programs.

The Burbio database includes 190 charter organizations—ranging from the IDEA Public Schools network with nearly 50,000 students to single charter schools with fewer than 1,000. About half of these schools are planning to invest federal money in summer learning or in summer and afterschool combined, collectively designating $33 million in ESSER III aid. KIPP DC is partnering with the Washington Nationals and Headfirst Sports Camps for its four-week, pre-K-8 summer program. Friendship Public Charter School in D.C. is offering an Inventors Playground Camp to teach STEM lessons to pre-K to grade 3 students in a recreational setting.

[Read More: How Local Educators Plan to Spend Billions in Federal Covid Aid]

*The Burbio sample includes 68 percent of U.S. public school students. It is somewhat overweighted toward large, urban districts, although the demographic characteristics of the student population are otherwise similar to nationwide trends, meeting the U.S. Education Department’s standards for a representative sample. It includes only 4 percent of the nation’s charter school organizations and 14 percent of the charter students.