This commentary was originally published in The 74.

School climate and student engagement surveys can tell us a good deal about important contributors to student success. They can illuminate students’ sense of belonging at school and their sense of themselves as learners. They can shed light on bullying among students, relationships with teachers and the respect a school shows for cultural and racial diversity.

But can these surveys be used to assess school quality?

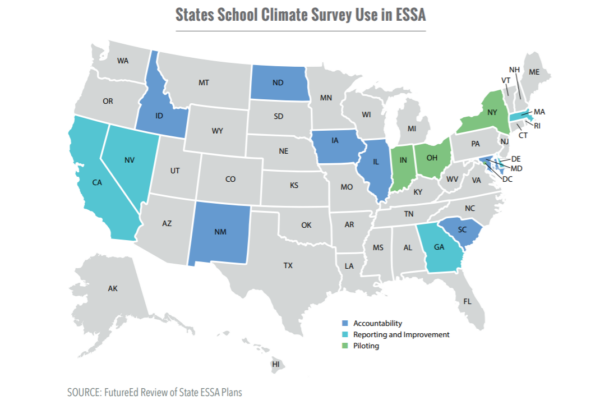

It’s a question that about a dozen states are testing as they factor survey results into their ratings for schools under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). Eight states are using surveys directly in their accountability rubrics, weighing the results alongside test scores and other metrics to determine if schools need improvement, according to an analysis by FutureEd at Georgetown University. Another five are reporting the results in federally mandated report cards or requiring their use in struggling schools.

This comes despite researchers’ concern that these tools are not intended for accountability purposes and are not yet reliable enough for comparing school quality. Many researchers and policymakers also fear that attaching higher stakes to surveys could tempt schools to manipulate results, reducing their value to school leaders.

[Read More: Walking a Fine Line: School Climate Surveys in State ESSA Plans.]

That happened in some places when standardized test scores became the coin of the educational realm in the No Child Left Behind era, and some policymakers worry that statistics on chronic absenteeism could suffer a similar fate as it gains currency as a measure of school performance. But those indicators at least are grounded in numbers.

Surveys record self-reported information and already subject to a number of biases. The interest in using surveys — of students, teachers and parents — to assess school quality represents the convergence of two trends: the recognition of the role that school climate and social-emotional development play in student success and the requirement under ESSA to include a nonacademic indicator in accountability rubrics. States that chose surveys typically combine the results with other metrics, such as chronic absenteeism or suspensions. And most are assigning relatively little weight to the results — a wise move, given questions about their validity.

Certainly, researchers and educators have identified valid uses for the information generated from surveys. For instance, researchers have found preliminary evidence that surveys can identify schools’ differing contributions to constructive climates and students’ social-emotional development. In California’s CORE Districts, a consortium of urban districts that surveys nearly a million students a year, the results correlate with both test scores and nonacademic measures, such as chronic absenteeism, and show promise in informing school improvement.

[Read More: CORE Lessons: Measuring the Social and Emotional Sides of Student Success]

But researchers and policymakers are still teasing out how best to use survey scores for informing school-improvement decisions. And they don’t believe they know enough to use the data for accountability.

Thus, the CORE Districts have steered clear of using survey results to hold schools accountable. And California did not include the tools in its rubric, opting instead to allow schools to report survey findings of their choice on the new California School Dashboard.

Likewise, some states that have administered surveys for years chose not to include them in their ESSA rubrics. “There was a pretty overwhelming agreement that these were metrics that could be gamed,” Pennsylvania Secretary of Education Pedro Rivera told me recently. “We didn’t want to disincentivize the collection of valuable data.”

Potential biases that creep into surveys include students reporting what they think they should be doing (such as turning in homework regularly or being polite to adults) rather than what they actually do; reflecting the characteristics of their friends or the norms of their school; and reacting to inherent stereotypes based on gender, race or class.

States that have chosen to include surveys in their accountability rubrics or report cards can take steps to protect their integrity. First, they can assign only modest weight to survey results, as most states have done, or award points for administering surveys rather than report survey scores.

They can invest in training teachers and other key school staff in how to interpret the results in ways that will improve student success, including providing guidance on the appropriate ways to use surveys, so teachers don’t unintentionally promote certain responses or use results to single out students in a racial or ethnic group that expressed negative views. And they can use the data they collect to continue studying whether surveys are a valid and reliable way to measure school quality.

While it is encouraging that states are recognizing the value of school climate and student engagement, surveys should be handled with care.

Phyllis W. Jordan is editorial director of FutureEd and co-author of the recent report Walking a Fine Line: School Climate Surveys in State ESSA Plans.