At a time when families are losing jobs and wages to the coronavirus crisis, college affordability has become an even greater priority than before the pandemic struck.

Yet states are facing revenue declines in a shrinking economy and can ill afford to subsidize families’ college costs. Not surprisingly, the sudden economic downturn has stalled the nationwide expansion of states providing at least two years of college tuition free. But a close look at the free-college landscape suggests that the popular programs may well survive the COVID crisis.

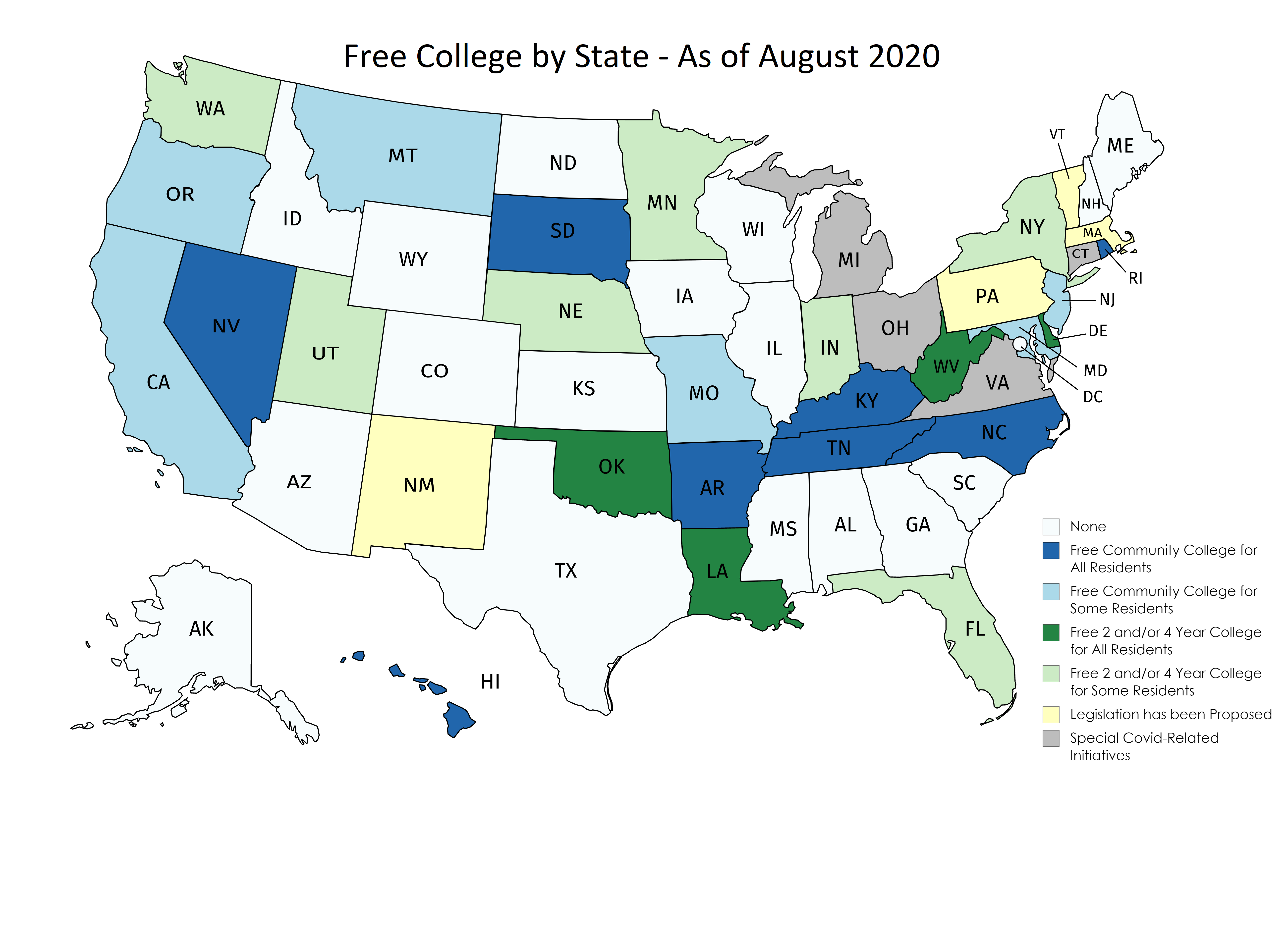

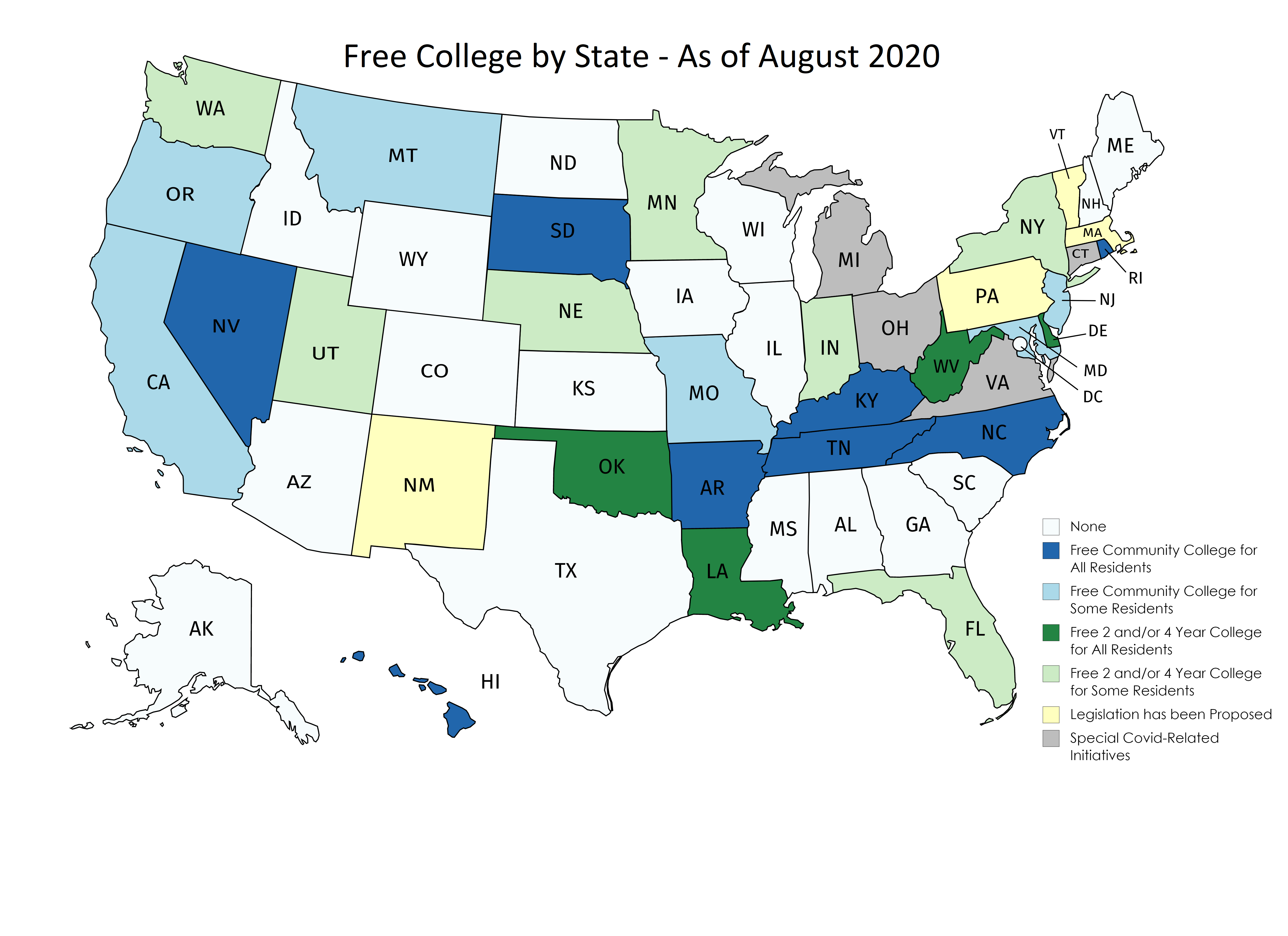

Before the pandemic, the free college movement was gaining ground. In the past two years, Washington, Virginia, Nebraska, and Utah passed new laws launching or expanded existing programs, and more than half the states had some sort of statewide program by last spring.

Other states—including Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Mexico, Pennsylvania and Vermont—proposed bills to establish or expand programs earlier this year.

But most of those bills stalled after the coronavirus outbreak. And in Virginia, which had become the latest state to approve a free community college program in March, the governor put the program on hold in April.

Programs that rely on state income or sales tax revenue, as most statewide free college programs do, are particularly vulnerable to cuts, as Martha Kanter, CEO of College Promise, an organization that promotes free-college programs, wrote in a July policy brief. To protect the programs, Kantor urged that both statewide and smaller local programs diversify their funding through entitlements, endowments, or financing tied to redevelopment or other projects. Tennessee’s statewide program, for instance, is funded with lottery revenue, which is expected to grow during the pandemic.

But if the Great Recession is a guide, the programs may be more insulated from cuts than other higher education spending. In 2018, Jen Mishory, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, looked closely at six existing statewide programs and found that funding levels per full-time equivalent student for all six existing Promise programs increasedbetween 12 and 142 percent in and around the time of the 2008 economic downturn, while overall appropriations per full-time student for higher education fell in each state between 18 and 38 percent.

[Read More: Education Spending in Congressional Covid Proposals]

Even now, some states are finding ways to expand access, albeit temporarily. In Connecticut, where legislation passed in 2019 but without any dollars allotted, the state’s Board of Regents for Higher Education agreed in June to spend $3 million to pay community college tuition for any first-time college student who graduated from one of the state’s public or private high schools. The sum represents one-time spending, so the program would need legislative support to continue past the coming school year.

“With the economic effects of the pandemic lingering, the opportunity for individuals to access a community college education is more imperative than ever,” said David Levinson, Interim President of Connecticut State Community College.

Other states are looking for ways to target spending to students most affected by the pandemic. After shelving plans for a broader “college promise” program, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer announced the launch of the Futures for Frontliners program, offering tuition-free opportunities to re-train essential workers. The program will be funded with federal Covid-aid dollars provided in the CARES Act,

Northam used some of his discretionary Covid aid provided by Congress to reinstate a small part of the program for displaced workers. In Ohio, Cuyahoga Community College recently offered free tuition to new and returning students struggling financially because of the pandemic. This includes people who lost a job or income due to Covid-19.

And help might be on the way from Washington. Likely Democratic Presidential nominee Joe Biden has embraced a federal-state partnership to expand the number of free-college programs.

Rachel Grich worked as a research associate for FutureEd for two years.