Since the school shooting in Parkland, Fla., a month ago, school safety has dominated the news. The House passed a bill Wednesday providing $500 million in grants over 10 years designed to make schools safer. The same day, millions of students nationwide walked out of school to demand action on gun violence. And the Federal Commission on School Safety will soon begin its work, led by U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos.

While the commission is likely to focus on such issues as gun control and racial disparity in school suspensions, it could take a small but significant step toward improving school safety by urging the end of school-sanctioned corporal punishment: paddling students.

Decades of observational and epidemiological research suggest that paddling’s longer-term effects are hardly compatible with public health and safety goals, or as DeVos put it during her 60 Minutes interview this month, “an opportunity to learn in a safe and nurturing environment.”

The practice is correlated statistically with increased aggression, antisocial behavior, criminality, adult abusive behaviors, and risk of suffering abusive relationships in adulthood. The recipients of paddling also tend to have decreased mental health outcomes relative to non-paddled peers.

Paddling entails a principal or a designated staff member repeatedly striking a student on the buttocks with a wooden paddle or open hand, causing pain in hopes of changing the student’s behavior.

The practice is much more widespread in schools than one may think: Nineteen states condone corporal punishment in public schools. In the 2013-14 school year, that meant 109,000 students were paddled in 4,000 schools, according to the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights data. And paddling is legal in private schools in nearly all states.

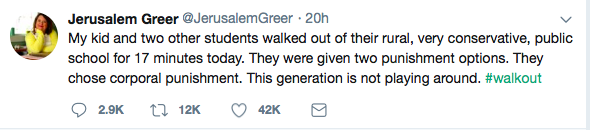

In fact, one Arkansas woman tweeted that her  son’s penalty for walking out of his public school Wednesday to protest gun violence was corporal punishment.

son’s penalty for walking out of his public school Wednesday to protest gun violence was corporal punishment.

The American Academy of Pediatrics came out against spanking 20 years ago. Many countries have banned paddling of children at home, in private schools, and in public schools. So have Jacksonville, Atlanta and other cities in states that permit the practice. Education Secretary DeVos would be wise to have her commission hear from leaders in such cities.

One issue she’ll likely encounter is the complexity of gender roles in corporal punishment. Many states and localities now prohibit male educators from paddling female students. But who paddles transgender students? It would surely be a question for the courts.

Because research suggests corporal punishment is more likely to increase rather than decrease aggressive behavior in schools, and because it is increasingly likely to be a legal thicket for schools, the new federal commission would be wise to recommend that policymakers abandon the practice of paddling in the nation’s schools.