With the rise of populism, advocates are questioning whether idea-centered change organizations such as think tanks still matter in securing policy wins. As part of the AdvocacyLabs initiative, Marc Porter Magee of 50CAN explores that question with John Campbell, the Class of 1925 Professor and Professor of Sociology at Dartmouth College and an expert on the ways ideas influence policy. He is the author of American Discontent: The Rise of Donald Trump and Decline of the Golden Age and the co-author of The National Origins of Policy Ideas: Knowledge Regimes in the United States, France, Germany, and Denmark.

Porter Magee: You have been a leader in exploring how ideas shape policy and politics. What is the most important thing you have learned about social change?

Campbell: One of the most important insights is that institutions are sticky, they slow down the process of change and conserve the existing order. That’s in part because people get used to them and take them for granted. But they also produce constituencies that benefit from them and those beneficiaries will work hard to stop anyone trying to change them.

Given that, how should advocates think about the opportunities to secure change?

There are four ways you might answer that question.

One is that there isn’t much change, that the status quo prevails. Its perhaps not the answer advocates are looking for but you could argue that it’s the most obvious answer given how often change efforts fail to achieve their goals.

Two, when you do have change, it tends to be very incremental, maybe two steps forward, one step back.

Three, change does happen but only when there is a crisis that upsets the apple cart. We call this a “punctuated equilibrium framework,” which is a phrase borrowed from evolutionary biology. This suggests that we will have long periods of stability that once in a while are disrupted by big shifts.

And the fourth and final answer, one that I tend to subscribe to, is that change is contingent. Sometimes no change is possible. Sometimes the only path forward is incremental change. Sometimes it’s a punctuated kind of a process. But rarely do you get anything brand new.

Can you give an example of that?

One interesting historical example is the post-communist transitions back in the early 1990s. The media talked about these as being revolutionary changes, but in fact, if you looked closer, they contained lots of bits and pieces of old ways of doing things that were just rejiggered and recombined.

The post-Soviet societies and their institutions did look new at first glance but they were strongly influenced by the past. Sometimes this is referred to as bricolage, a recombining of already existing pieces. Advocates should understand that while institutional change comes in a variety of different forms, you will almost never have the chance to create anything that is brand new, even in a so-called revolution.

How should we think about the role of experts in driving these changes? Has the new upswing in populism made experts less relevant?

The role of experts has changed over time, and in some ways is less important in driving change. But they still matter. I guess the metaphor when drafting white papers or reports might be like throwing spaghetti against the wall. Less sticks than it used to, but some does and it’s just hard to know which until you do it.

Expert-driven change sounds very messy, which is perhaps fitting for our age.

Yes, and this is particularly so in the United States. We live in a marketplace of ideas, and it’s incredibly competitive. Sometimes experts have tremendous influence. And sometimes they have very little. Some are successful, some are not. The real test of influence is not whether you are generating ideas, but whether the people in power are listening to you.

Of course, one of the people in power right now is Donald Trump. What would it mean for the future of expert-driven change if we ended up with more politicians like Trump?

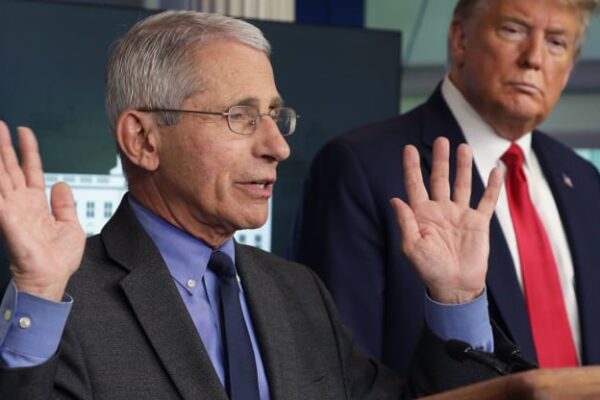

We probably shouldn’t overstate the degree to which expertise mattered in the Obama administration. But there is one big difference between Trump and previous administrations, which is that he reacts much more unpredictably from the gut. This is especially clear in how Trump has often ignored the advice of health policy experts during the coronavirus pandemic.

With Obama, Bush and Clinton, there was always a set of experts who would play some role in helping them form policy, for better or worse. That doesn’t mean they always gave good advice, but these were serious, well-educated people who presidents would often listening to before making a decision. That gave people trying to influence the president with research and ideas a way to do so.

Do think tanks and researchers matter in a world where decisions are made from the gut?

It’s sort of a grab bag. There are two reasons funders keep giving to think tanks. One is the direct way they are interacting with policymakers. They produce and distribute reports and white papers. They provide testimony. And all of that matters, up to a point.

The other way is how they are shaping how we think about and talk about a topic, which in some ways is more powerful. You see a lot of funders, for example, giving money to universities to influences the realm of ideas and ideologies. It is harder to measure, but I think those strategies have been pretty successful. And it doesn’t require a politician to read a white paper because the whole way we talk about an issue has shifted. Of course, that’s a long-term plan that requires decades of investment.

So if you were a funder investing in a cause, would you still give to the expert side of this advocacy work?

I would try to use as many strategies as I could afford and hope that one of them or two of them at any particular moment in time would actually hit the target. That way, if you have direct access to the policymakers, you are ready with the policy plans. If you don’t, you can still use research to drive the stories that will get picked up in the media, which is another way to reach the politicians. And in the meantime, you should always be working to shape and define the broader discussion of the ideas you care about and using a variety of other tactics to build up political will.

All the money in the world can’t guarantee change. But a combination of strategies—including ones driven by experts—increases your odds of success.