Student testing at the national, state and local levels has given policymakers a clear, up-to-date picture of learning loss during the pandemic. But on another key recovery metric, student absenteeism, reporting has lagged badly in many states, making it difficult to know if the hundreds of millions of dollars and thousands of hours states and school districts have spent to get kids back in school are working, and if policymakers should continue to invest resources to bring down absenteeism rates that spiked during the pandemic.

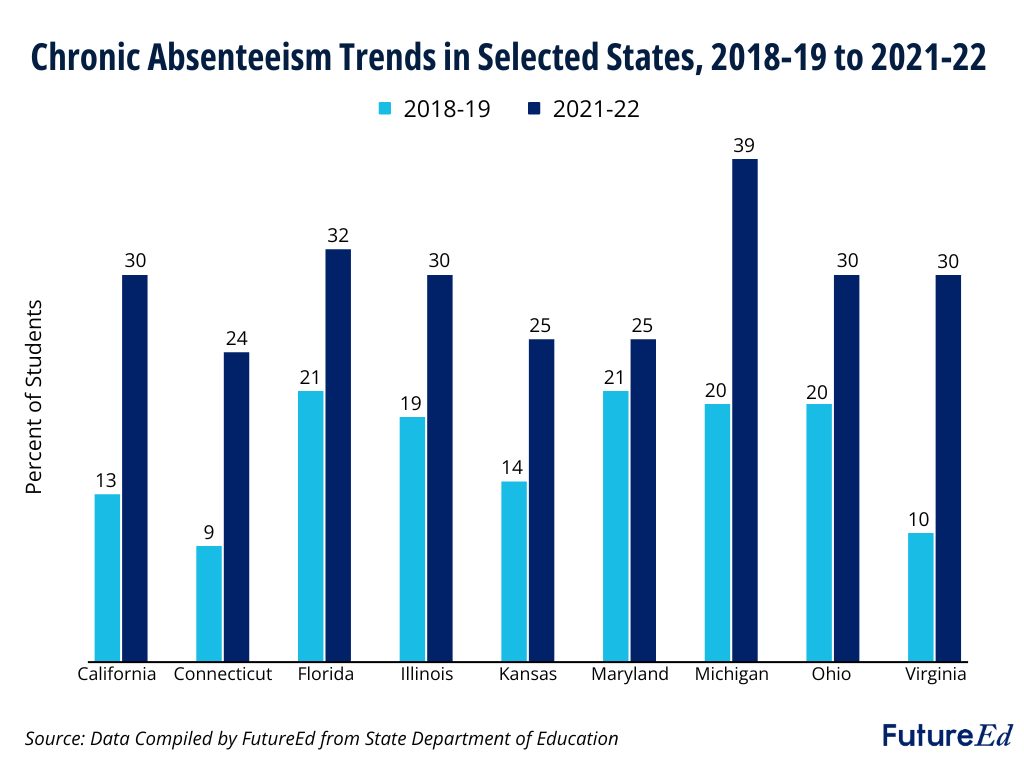

One of the most surprising and least anticipated consequences of pandemic school disruption is that many students didn’t return to school when normal operations resumed. In many districts, chronic absenteeism—the number of students missing 10 percent or more of school days—increased in the 2021-22 school year from the previous year, even after schools were fully open and vaccines were widely available. Michigan, for example, saw its chronic absenteeism rate almost double from 20 percent to 39 percent during the pandemic. Virginia’s rate tripled from 10 percent to 30 percent.

Long quarantines and other Covid protocols still enforced in 2021-22 undoubtedly contributed to the increases. But was 2021-22 an outlier, or part of a longer-term trend? In the absence of 2022-23 attendance data in many states, we don’t know. In at least 35 states, the most recent absenteeism information is now 15 months old.

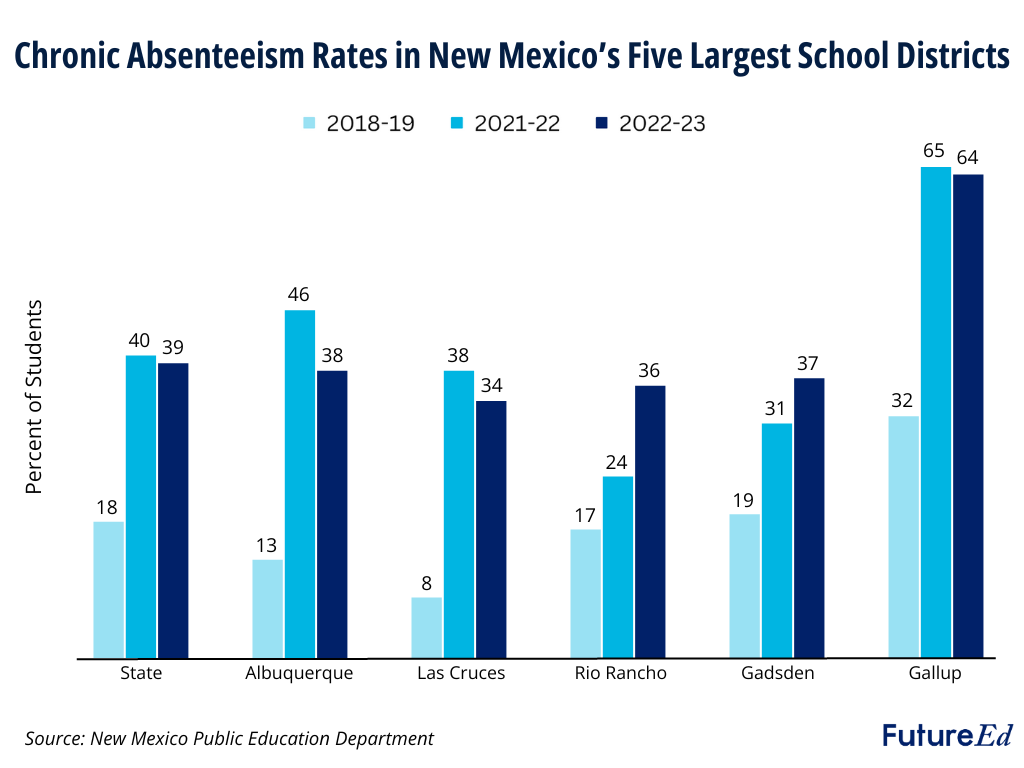

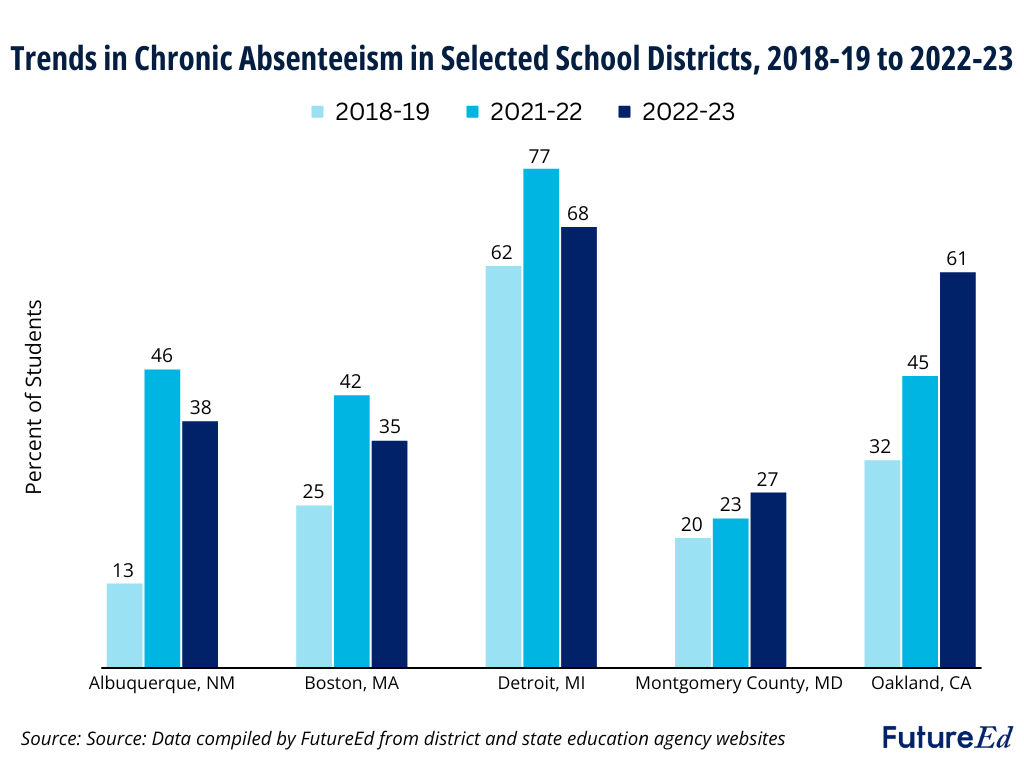

In the relatively few states and school districts that have released more recent information, the results are mixed; absenteeism is improving in some places and worsening in others. In New Mexico, where the state has made detailed 2022-23 chronic absenteeism data publicly available on its education department website, the statewide chronic absenteeism rate has declined slightly in the past year, from a staggering 40 percent to 39 percent. Absenteeism rates in the Albuquerque school district declined from 46 percent in 2021-22 to 38 percent in 2022-23. Just 15 miles north in Rio Rancho, however, the trend continues to move in the wrong direction, with chronic absenteeism rates rising from 24 percent in 2021-22 to 36 percent in 2022-23.

The same mixed picture exists in other jurisdictions that have reported numbers. Connecticut—a state that has dedicated millions of federal ESSER dollars to improving attendance through its Learner Engagement and Attendance Program that focuses on home visiting—has released 2022-23 attendance data showing a decline in chronic absenteeism statewide. But Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland and Oakland Unified School District in California both saw rates of chronic absenteeism continue to rise last year.

Knowing who’s in school post-pandemic and who isn’t is critical for legislators, local school board members and administrators, and states shouldn’t rely on thousands of local school districts to do the job. Tracking individual districts as they release data is inefficient. If Connecticut and New Mexico can produce 2022-23 attendance data in weeks, there’s no reason why other states can’t do so. Take Rhode Island. Recognizing that its traditional practice of reporting chronic absenteeism at the end of each school year “is often too late for schools and districts to help get students to school,” the state’s department of education has launched a Rhode Island Student Attendance Leaderboard that updates public reports on school-level attendance daily throughout the school year.

Knowing who’s in school post-pandemic and who isn’t is critical for legislators, local school board members and administrators, and states shouldn’t rely on thousands of local school districts to do the job. Tracking individual districts as they release data is inefficient. If Connecticut and New Mexico can produce 2022-23 attendance data in weeks, there’s no reason why other states can’t do so. Take Rhode Island. Recognizing that its traditional practice of reporting chronic absenteeism at the end of each school year “is often too late for schools and districts to help get students to school,” the state’s department of education has launched a Rhode Island Student Attendance Leaderboard that updates public reports on school-level attendance daily throughout the school year.

But too many states haven’t even announced when last year’s data will be available. South Carolina and the District of Columbia, for example, won’t release 2022-23 attendance data until November 2023. It raises the question of whether states are deliberately slow-rolling unflattering information. If states like New Mexico and Connecticut have released encouraging absenteeism results, are other states withholding less-encouraging news?

States that have released 2022-23 chronic absenteeism data as of September 22, 2023: Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Rhode Island, Virginia, and West Virginia.