This commentary was published in The Hill.

The pandemic relief package that passed earlier this month includes no less than $126 billion for schools, and there’s talk in education circles of using a portion of the money to reduce class sizes by hiring thousands of teachers to increase social distancing in schools.

But scattered teacher shortages in parts of the country and in subjects like math and science raise the question of where the new teachers would come from. And paying teachers tens of thousands more once federal funding dries up will be difficult, likely creating the potential for widespread post-pandemic layoffs.

A smarter strategy for helping struggling students, both during and after the pandemic, would be to deploy existing staff more creatively than most schools do now. As it happens, some schools, school districts and charter school networks have been doing just that since the nation’s schools closed a year ago. By abandoning the traditional notion of what it means to teach — standing before the same roomful of students day in and day out for the duration of a school year — they have forged new staffing models and school schedules that play to teachers’ strengths, address shortages in key subjects and enhance learning.

One reason distance learning has been such a harrowing experience during the pandemic is that most schools merely shifted the traditional teaching model to online platforms. In contrast, some schools and school districts sought to use technology to their advantage.

[Read More: Teaching Innovation: New School Staffing Strategies Inspired by the Pandemic]

Frequently, they have worked to get their best teachers in front of more students. That’s what a group of former charter and traditional school district officials sought to do when they launched a nonprofit organization at the outset of the pandemic called Cadence Learning.

They hired a national team of distinguished educators to record lessons in front of a group of students and then send the lessons to schools serving 8,800 students in 11 states and Washington that partnered with Cadence. Teachers in the local partner schools play the recording for their students or teach a version of the lesson themselves, using virtual breakout rooms to work with their local students in small groups.

The local teachers like the partnership and the vast majority of them reported to University of Virginia researchers that their students improved their academic abilities during Cadence’s program last summer. Students also rated the experience highly.

Another strategy puts top teachers in charge of instructional teams serving multiple classrooms as a way to distribute teaching responsibilities based on teacher strengths and increase teacher-to-teacher support.

The nonprofit Public Impact has helped introduce the concept in 45 school districts and charter management organizations in 10 states, where lead instructors manage as many as eight teachers, paraprofessionals and teacher residents in the same grade or subject. These team leaders coach teachers and track students’ progress while earning larger pay checks. Before the pandemic, a national study found that the teaching teams boosted students’ math and reading results significantly.

Other schools have rethought traditional class sizes and school schedules. A suburban Cleveland elementary school shifted to having students in each grade take art, music, physical education and other special subjects on a single day every week during the pandemic, giving classroom teachers in each grade an entire day to plan together. At a Minneapolis high school, teachers shifted its schedule after realizing students were overwhelmed by remote learning. The new model at a project-based learning academy within Patrick Henry High School concentrates instruction in each subject, making students’ schedules much simpler.

Kairos Academies, a St. Louis charter middle school, operates on a seven-week cycle year-round: Students attend school for five weeks and are off for two; staff have one week off and another for training and planning

Despite the promise of such innovations, there are substantial barriers to scaling them. Reluctant teacher unions and rigid labor contracts are among the toughest. It’s not only in-person instruction that the American Federation of Teachers and the National Education Association and many of their affiliates have resisted during the pandemic.

Some education authorities have managed to work with unions to make change happen, such as the Springfield Empowerment Zone in Massachusetts. The network of 15 low-performing schools, established to avoid a state takeover, had built flexibility into its agreement with the local union before the pandemic began.

When schools went virtual last spring, Zone leaders recruited the best teachers in different content areas to develop asynchronous lessons that all students in the Zone could access remotely. That enabled teachers in each school to focus on individual and small-group support for their students, like the Cadence model.

But the Springfield Education Association’s response to the pandemic has been an outlier in large school districts. An analysis by the National Council on Teacher Quality of COVID-19-related memoranda of understanding between labor and management in major districts found language on requirements for live instruction, health and safety protocols and other logistical topics, but none related to new staffing structures.

Beyond union resistance, regulations regarding mandatory class size, teacher licensing, bell schedules, required instructional minutes and the length of the school day and year also impede staffing innovations, as does standard school budgeting.

While the pandemic has slowed the learning of many students, it also has highlighted flaws in many traditional educational practices and has encouraged new ways of delivering education that tap teachers’ strengths and improve schools’ productivity rather than merely expand their payrolls, valuable strategies both during the pandemic and after it has subsided.

Thomas Toch is director of FutureEd, and Lynn Olson is a senior fellow.

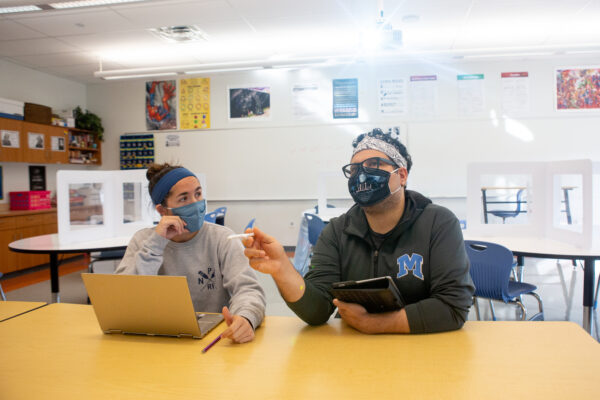

Photo courtesy of Allison Shelley/The Verbatim Agency for American Education: Images of Teachers and Students in Action.