Most parents know the frustration of asking their early adolescent son or daughter how their school day went and receiving an eye-roll in response. As children transition from elementary school to middle school, it’s not uncommon for them to become less communicative as they seek to develop more of their own identity and personal space.

That means that parents must rely heavily on report cards and other school communications to know if their children are thriving. But too often communications between families and middle schools break down. Nearly nine in 10 parents believe their child is at or above grade level in reading and math, despite the reality that barely a third of students perform at that level.

Middle school teachers have more students—and, therefore, less time—to communicate with families. Because parents want their children to gain agency and independence, they typically pull back from direct interactions when students reach middle school.

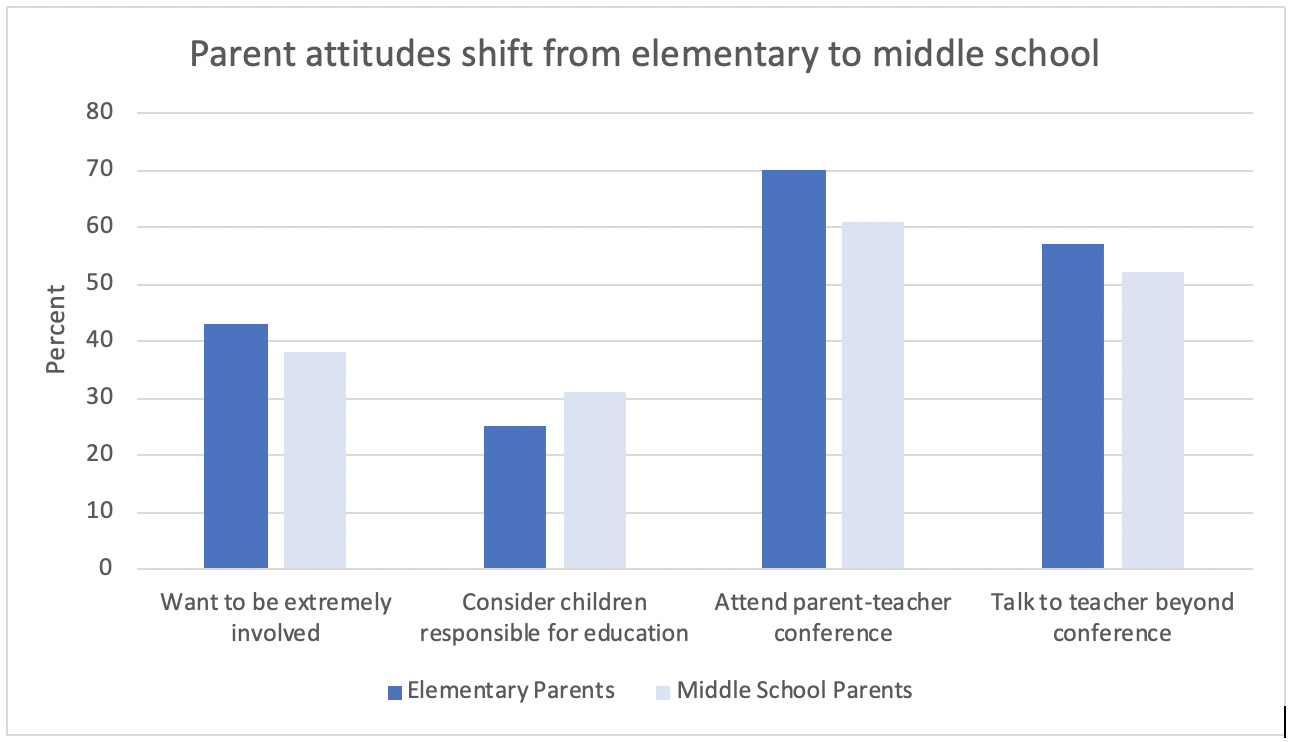

Learning Heroes’ nationally representative survey of parents and teachers of public school children in grades 3-8, Parents 2018: Going Beyond Good Grades, found that both parents and teachers invest less in home-school communications during the middle school years.

Yet middle school is a key time for parents and schools to join forces to support young adolescents’ healthy social, emotional, and academic development. Puberty-related hormonal changes launch a period of intense brain development—the most dramatic period after infancy—that makes the brain more vulnerable to the effects of stress. While this is a time of cognitive and psychological growth, it’s also a time when young people may be vulnerable to mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety. And it’s a time of heightened sensitivity to peer pressure, social cues, and physical appearance.

Not surprisingly, surveys by the CORE Districts in California and others have found that students’ sense of self-confidence drops after elementary school and then recovers in high school. Yet 68 percent of parents that Learning Heroes surveyed reported their children are very or extremely happy.

[Read More: CORE Lessons: Measuring the Social and Emotional Dimensions of Student Success]

There are legitimate challenges to home-school communications during the middle years. Parent-teacher conferences often become optional, with some parents referring to them as “speed dating,” given the number of students that teachers see. Parents are less likely to see—or be able to help—with homework or classwork. Given teachers’ course loads, many parents feel reluctant to reach out unless there’s a real problem.

To address these challenges, Learning Heroes has developed a conversation starter designed with parents and educators that that brings parents, teachers, and children together to build a more complete and accurate picture of a student’s developmental and academic progress.

Other strategies include student-led parent-teacher conferences that give students a proactive role in communications between parents and teachers, and student exhibitions of middle school projects that let parents see firsthand what their children are accomplishing. Let’s give parents more ways to track their children’s learning and growth, making those middle school years a little less of a mystery.

Bibb Hubbard is founder and president of Learning Heroes, a nonprofit dedicated to helping parents advocate for their children.