We demand a lot from teachers. We expect them to have a deep and broad understanding of what they teach and whom they teach, because what teachers know and care about makes such a difference to student learning.

But the current coronavirus crisis reveals that we expect much more from our teachers than delivering lessons. We also expect teachers to be passionate, compassionate and thoughtful; to encourage students’ engagement and responsibility; to respond to students from different backgrounds with different needs, and to promote tolerance and social cohesion; to provide continual assessments of students and feedback; and to ensure that students feel valued and included. And we expect teachers themselves to collaborate and work in teams, set common goals, and plan and monitor the attainment of those goals.

But how do we know if they’re succeeding? And who decides who is getting this right? The answer is teacher appraisal, a practice that is embraced across the globe. An Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) survey of 260,000 secondary school teachers and administrators worldwide shows that increasingly there are consequences attached to these evaluations.

The second volume of the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS), which was released in late March, found that only 7 percent of teachers work in schools where they are never appraised. About two thirds (64 percent) say their appraisals are most often conducted by the school principal, with others getting input from a school management team or other teachers..

In nearly all TALIS countries and economies, more than 90 percent of teachers say their work is evaluated based on classroom observations, as well as on students’ academic results. Many places rely on student survey responses related to teaching (82 percent of teachers), assessments of teachers’ content knowledge (70 percent) or self-assessments of teachers’ work (68 percent). TALIS findings indicate that, on average across the OECD, teachers who are evaluated work in schools using five of the six different methods.

Nearly all the teachers report that appraisal is “sometimes,” “most of the time,” or “always” followed by a discussion with the principal about any weaknesses in teaching. About 90 percent say that includes plans for professional development, and in seven out of 10 cases it can lead to an appointment of a mentor or a change in work responsibilities.

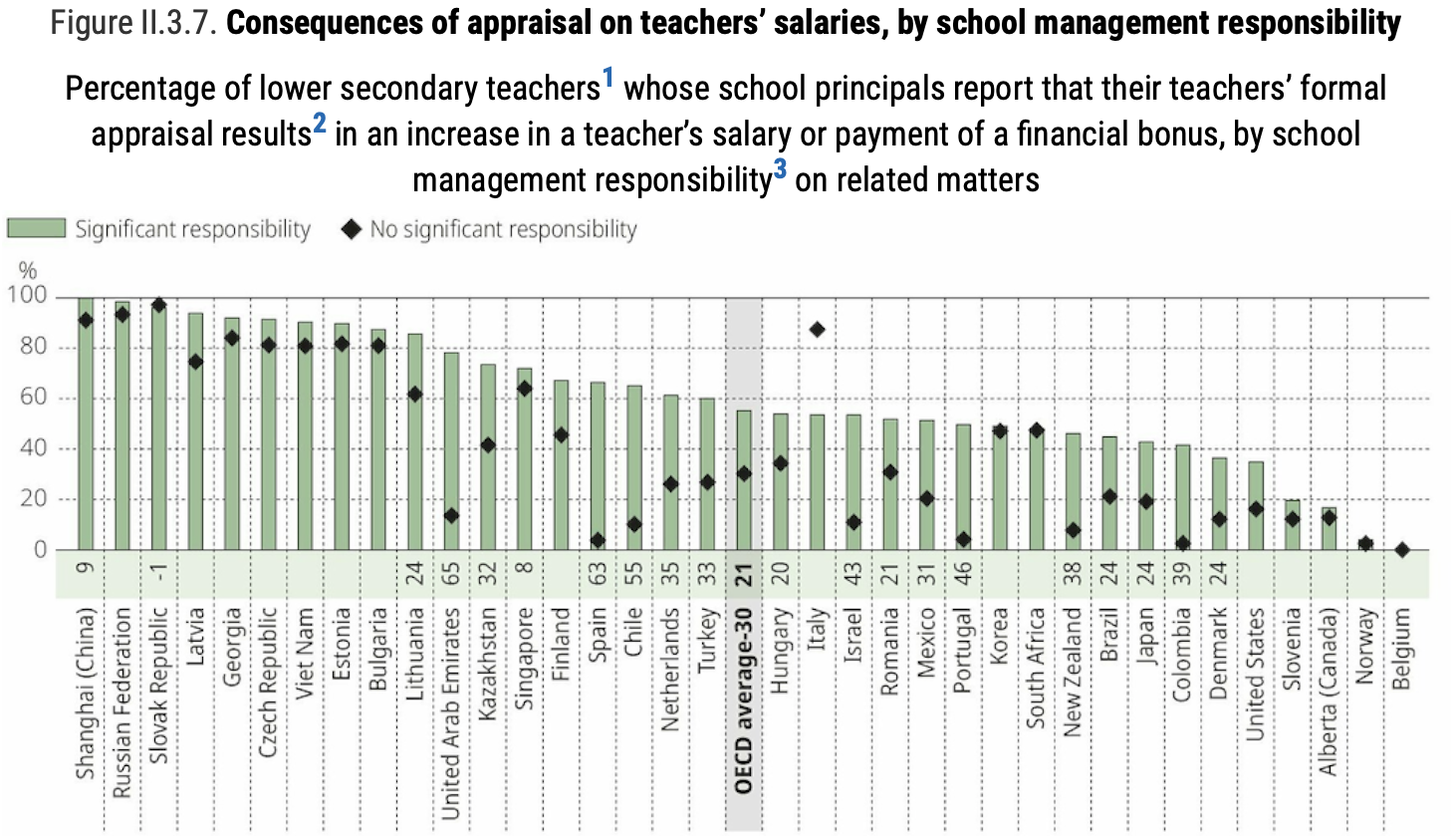

High-stakes consequences are less common: About half the teachers report that a poor appraisal can lead to changes in career prospects, dismissals or non-renewal of teachers’ contracts, but only 15 percent say it could lead to reduced pay increases. About two out of five say a good review can lead to increases in salary or financial bonuses.

That said, the number of teachers reporting consequences for their evaluations ratcheted up in the five years between the TALIS surveys in 2013 and 2018, particularly tying appraisal results to financial rewards and career advancement decisions. Overall, the changes suggest a growing reliance on financial and career advancement incentives as policy levers, as well as on support to teachers through mentoring, and a declining reliance on changes in teachers’ work responsibilities, dismissals and contract non-renewals.

This was particularly true when the school management team—the principal and other leaders—had “significant responsibility” for those consequences. Interestingly, U.S. teachers were less likely than the OECD average to report salary consequences for appraisal when principals have significant responsibility.

The Singapore Model

The Singapore Model

Few education systems combine these features as systematically as Singapore does. The system there has three components: a career path, recognition through monetary rewards, and an evaluation system. The system recognises that teachers have different aspirations and provides for different career tracks for teachers.

Performance management in Singapore is competency-based, and defines the knowledge, skills and professional characteristics appropriate for each track. The process involves performance planning, coaching and evaluation. In performance planning, the teacher starts the year with a self-assessment and develops goals for teaching, instructional innovations and improvements at the school, and professional and personal development. The teacher meets with his or her reporting officer, who is usually the head of a department, for a discussion about setting targets and performance benchmarks.

Performance coaching takes place throughout the year, particularly during the formal mid-year review, when the reporting officer meets with the teacher to discuss progress and needs. In the performance evaluation held at the end of the year, the reporting officer conducts the appraisal interview and reviews actual performance against planned performance.

[Read More: The Path to Professionalizing Teaching]

The grade given for performance influences the annual performance bonus received for the year’s work. During the performance-evaluation phase, decisions regarding promotions to the next level are made based on “current estimated potential.”

The decision about a teacher’s potential is made in consultation with senior staff who have worked with the teacher. It is based on observations, discussions with the teacher, portfolio evidence and the teacher’s contribution to the school and community.

Lessons Learned

Examining the results from TALIS and studying appraisal systems across education systems, the OECD has learned several important lessons.

First, the success of an appraisal system depends on clear alignment of its processes, methods and tools with the goals pursued. The first step of any review of appraisal mechanisms should be for policymakers and school leaders to clearly prioritize and define key objectives, such as compliance with standards, the formative development of teachers, and reward mechanisms for good performance.

Second, the characteristics of the appraisal system should align with these key objectives and policy priorities. For example, if the main function of teacher appraisal is to inform career decisions and strengthen accountability, then it must be based on defensible and comparable sources of evidence and combine multiple standards-based measures to evaluate teachers accurately and fairly on the variety of tasks composing their jobs.

[Read More: The Education Imperative in a Digitized World]

If the main goal of appraisal is to inform professional development and promote learning, then teacher observations and self-evaluation can provide valuable tools to spur teachers’ self-reflection and achieve this formative goal.

Third, it is important to ensure that the consequences of appraisal are also aligned with these goals. For instance, consequences such as a follow-up exchange, elaboration of a professional development or training plan or appointment of a mentor are more likely to generate a virtuous cycle of formative appraisal and school improvement. Conversely, performance incentives such as wage increases, financial bonuses or even dismissal of a teacher are more likely to be effective if the goal is to ensure good performance and compliance with standards.

Schleicher is Director for Education and Skills and Special Advisor on Education Policy to the Secretary-General at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.